Tang Chang

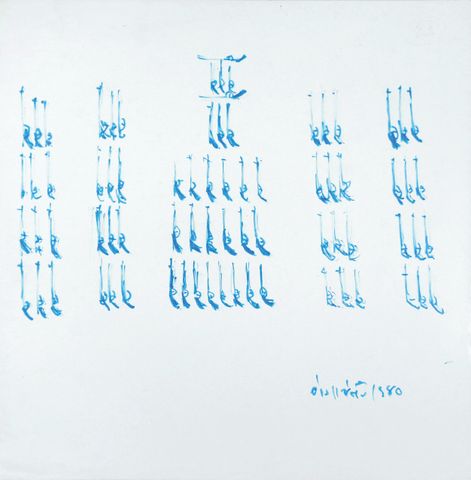

Tang Chang (also known as Chang Sae-tang) was born into a poor Chinese family in Bangkok in 1934. A lifelong autodidact, he started drawing at the age of nine. He spent most of his childhood in and around the temple near his home; a local monk became his mentor, feeding his curiosity about philosophy and Buddhism. Chang’s education was interrupted by the Second World War and he could not continue beyond primary school, but took an interest in the Chinese language and managed to attend some night school classes. As a youth, he did various jobs and from the age of sixteen, earned a little money drawing realistic portraits in charcoal. His artistic career started in the late 1950s. A fascination with nature saw him favor landscapes, which he rendered mostly in watercolors on paper – cheap and accessible materials that were to be the mainstay of his creative life. Shortly after he introduced non-figurative elements into these landscapes, alongside more abstract experiments in ink, and by the early 1960s, had started working on raw canvas. This became the basis of the abstract, calligraphic paintings for which he would be best known, made with a gestural spontaneity previously unseen in Thai modern art.

Chang received invitations to lecture at universities and exhibit in galleries and cultural institutions from the mid-1960s, but did not allow his works to enter the market and remained staunchly independent of the Thai art scene. Though he worked on its fringes, he was respected and befriended by some of its most influential figures including Pratuang Emjaroen, Paiboon Suwannakudt, and Kamol Tassananchalee. Striving to make his work accessible to a wide audience, he encouraged young students, and art and poetry enthusiasts, to study informally with him. He mentored several innovators of the next generation including Phaptawan Suwannakudt and Somboon Hormtienthong.

Chang paid little attention to the divisions between art forms, moving intuitively between painting, drawing, and literature. In 1967, he began to write creatively, though he knew little about poetry. He used repetition to express movement and feeling, and this became a daily practice, which would be described as “concrete poetry.” Recognized as a maverick who overturned prevailing conceptions of Thai poetry, Chang communicated profound insights with formal simplicity and plain language. His interest in Chinese philosophy and literature deepened in the early 1970s. He began to translate and publish classical texts, making their ideas available to a general readership through simplification, commentary, and explanation.

In 1985, towards the end of his life, Chang opened a small museum at his residence, which he named “Poet Tang Chang’s Institute of Modern Art.” He exhibited his own works there, and it became a gathering place for his artist friends, poets, students, and art lovers. When the family was forced to demolish the house just three years later, he regretfully closed his private museum. Chang passed away in 1990, leaving an extraordinary legacy in the care of his family.

Mary Pansanga