Bagyi Aung Soe

In the emerging history of art in twentieth-century Myanmar, Bagyi Aung Soe (1923–90) is regarded as the trailblazer of modern Burmese art. He began as a dilettante in the 1940s, aspiring to be a politically and socially conscious cartoonist. His inventiveness and flair as a draftsman caught the attention of Myanmar’s literary giants – Dagon Taya (1919–2013), Min Thu Wun (1909–2007), and Zawgyi (1907–90) – who commissioned him to make illustrations for the literary magazine Taya and recommended him for an Indian Government Scholarship to study at the Visva-Bharati University founded by Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). Their patronage catapulted the twenty-seven-year-old into the ranks of Yangon’s most promising artists.

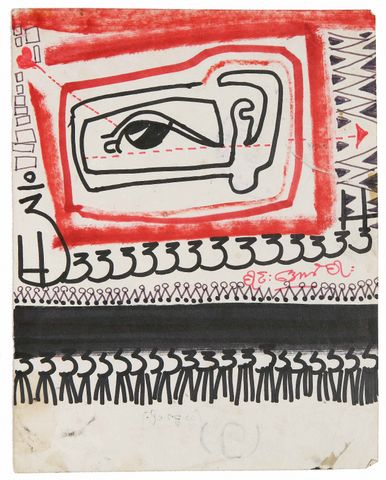

On his return in 1952, inspired by his Indian gurus, Aung Soe strove to create a contextually specific pictorial idiom. Without acceding to the hegemony of Western modernism, he experimented with Western avant-garde styles alongside other approaches, old and new, from various parts of the world. As he eschewed the commodification of art as an elitist luxury – and as there was no art market in Myanmar anyway – illustration became the principal site of his practice and his platform for bringing art to the masses. Throughout his four-decade career, he sought to boost his countrymen’s appreciation of art by writing in widely read periodicals. To the same end, he published in 1978 an anthology of illustrations entitled Poetry without Words, and a compilation of articles, From Tradition to Modernity.

Aung Soe’s nationwide fame was amplified by his success on the silver screen in the 1970s. Between 1962 and 1978, he also taught graphic art and art history at the Yangon Institute of Technology and Yangon University. Although ill health forced an early retirement from education and film, he continued to write and paint throughout the 1980s. In this last decade of his life, intensified meditation practice and research into Buddhist philosophy gave rise to his signature pictorial idiom, which he termed manaw maheikdi dat pangyi: the painting of the fundamental components of the phenomenal world through the powers of mental concentration.

Aung Soe’s legacy in Burmese art lies not in style or technique, but in the awakening of a novel artistic consciousness. His incarnation of the archetype of the impoverished and tortured genius, and his pursuit of an art allied with spiritual transformation removed from market concerns, earned him both the derision of Myanmar’s authorities and the respect of the country’s foremost intellectuals. In the writing of modern art’s histories beyond Euramerica, his singular conjugation of methods from different historical periods and traditions (including the natural sciences, popular culture, and ancient beliefs) compels us to rethink art history’s prevailing narratives and frameworks.

Yin Ker