1957: The Opening: Is this America?

“The Old and the New World” – Adorno, Thornton Wilder and Martha Graham at the opening

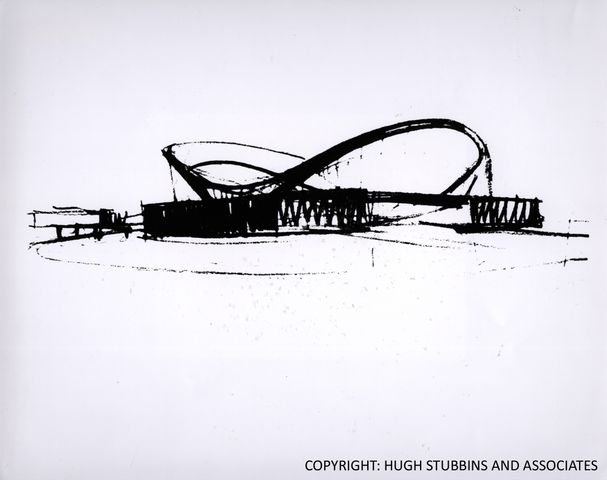

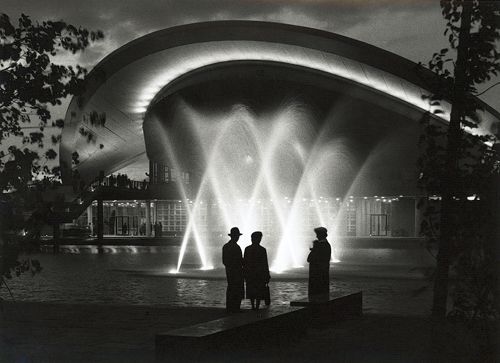

As is the custom when naming a ship, a bottle of champagne is smashed against one of the two pillars supporting the Congress Hall’s symbolic roof. On the morning of 19 September, five days of opening celebrations begin. Between the two pillars, the distinguished guests can see the white surface of the suspended reinforced concrete roof, its wings stretched over the curved side arches. Only a few days earlier, West Berlin newspapers were busily speculating whether everything would be ready in time. But architect Hugh Stubbins has achieved his goals. In 1954, after a disconcerting visit to East Berlin, he conceived the goal that would govern his design: to point the way forward, showing that boundaries can be transcended even in an “imprisoned” city, and that under a roof like this nothing can stop the emergence of new ideas. The emotional force of his design lies in its boldness and freedom. Ultimately, however, the structural engineers will find his idea too daring and insist that the roof be supported by a concealed auxiliary concrete ring. This support will trigger a heated discussion among Europe’s leading architects – and cause a catastrophe some twenty-three years in the future. What is known in 1957: the structure employs the most modern technology. The formal languages of the tent and the dome, currently being tried and tested in pioneering huge buildings at international airports and sports stadiums, are combined here – in a cityscape covered with ruins. The interior of the Congress Hall where the eminent guests are mingling fully satisfies the need for limitless communication: with spacious areas for interaction, cubicles for interpreters, radio and television facilities and telephone systems – a range of equipment that could, at the time, be found only at the UN Building in New York. Similarly, the auditorium was inspired by the United Nations General Assembly Hall.

The centrepiece of the opening celebrations is a cultural programme that includes concerts, plays and dance, a photographic exhibition and four rounds of discussions on the arts, science and education. One event, entitled “The Old and the New World”, focuses on transatlantic relations. Theodor Adorno, Thornton Wilder, Boris Blacher and Isamu Noguchi speak. These events respond to the demands of the symbolic architecture and the opening speeches in a way that surprises German critics. When classical music is performed, praise is heaped on the orchestra, the vocals and the acoustics of the new hall. But the contemporary American music upsets quite a few. And the series of seven one-act plays selected and hosted by Wilder meets with bewilderment. They are deemed “gloomy and monotonous”, with their small towns full of boredom, racial problems, criminals, and married couples on the verge of suicide. Is this meant to show the real America? And although Martha Graham’s dance is greeted with applause because of her body control, the German media maintain that it displays too little emotion and too much analysis. Overall, this was a very special kind of propaganda – or so it will seem fifty years later – and bound to provoke controversy.

As is to be expected, the opening speeches and the messages of greeting on 19 September are less controversial. They echo the tone set by the US Foreign Secretary in New York at almost exactly the same time. While his sister Eleanor is participating in the opening of the Congress Hall in Berlin, John Foster Dulles is taking part in a general debate at the UN, attacking the USSR over the growing division of Germany. On this particular evening, the country’s division is practically overcome by the thousands of onlookers from East Berlin who, according to West Berlin’s newspapers, have made their way to the new Congress Hall that evening and will be pressing their noses against the huge glass panes over the next few days.

Axel Besteher-Hegenbart

New York Times 25 June 57

Der Abend 10 Sep. 57

Berliner Morgenpost 20 Sep. 57

Der Tagesspiegel 21 + 22 Sep. 57

New York Times 21 + 29 Sep. 57