“The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born: in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

—Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (1971, p. 276)

There are two Siberian tigers (Panthera tigris altaica), also known as the Manchurian tiger or Chosŏn Horangi (the Korean Tiger), enshrined in the endangered species hall at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. These melancholic, stuffed reproductions of tigers as an ethereal spectacle of nonexistence, once had roamed the harsh mountain woodlands stretching from East Russia to the Korean Peninsula until the first half of the twentieth century, but are now all but vanished. According to Mary Linley Taylor (quoted in Green 2006), many hundreds of years ago, the ancient Mongol emperors designated hundreds of square miles of land north of the Tumen River near Vladivostok as a sanctuary for tigers imported from India. By culling the genetically superior and largest subspecies among the felids, Mongolians improved on the physique of the massive, light-colored Siberian tigers, which reached 4.25 meters in length and weighed over 250 kilos. After the sanctuary was abandoned, the tigers spread north to Sakhalin island and to the Korean Peninsula, and here they bred with the local tiger population, creating a massive subspecies.

The Siberian Tiger displayed in the Hall of Biodiversity at the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. © The author, March 2017

During the late nineteenth- to the early twentieth century in Korea, Siberian tigers were hunted and killed by Western trophy hunters, including the British sportsman and writer, Ford G. Barclay (co-author of The Big Game of Asia and North America, 1915), and Japanese colonizers under the varmint extermination project (害獸驅除事業 해수구제사업). An inhumane varmint extermination project was carried out under state law during the period of Japanese occupation, which declared “all animals harmful to human beings will be hunted.” The project, which was executed under the Governor-General of Korea, classified many of the native species of superior predators in the Korean ecosystem such as tigers, leopards, bears, and wolves as varmint. The classification meant that these species could be hunted year-round without a permit or any limit on the number killed. Meanwhile, the Korean landscape under Japanese rule transformed dramatically from an agrarian one into the vibrant modern topos of commoner life. All animals, including colonial Koreans, have been deeply conditioned by the radical transformation of their territories and modes of existence.

Within this complex, transitional time of modern Korean history, what do the Chosŏn tigers that ended up displayed under the dim lights of the American Museum of Natural History indicate to us? They can represent the dialogues between the human and nonhuman, concerning not only the displacement of the tigers’ diasporic afterlife, but also the range of generic and thematic convergences beyond the anthropomorphic and projective perspectives of these uncanny stuffed creatures as allegories—national, historical, and colonial—which germinate within the concealed structure of disjointed modernity. This non-decaying metaphor of tigers as continual coloniality that lingers on in my own experience as a subjective marginal historiographer in my writing—an extremely heterogeneous position compared to that of the objective historian—has given me an ambivalent empathy with which to rethink the intermingled past and present. This diplopic time of the animal and colonial life as nonhuman entangles with the memory of my once-colonized homeland, inviting me in, while simultaneously stimulating the unutterable discourse of the void of history and the loss of sovereignty among the colonized.

Recollecting Gramsci’s remark regards the interregnum of disjointed time and space as symptomatic of contemporaneity, the ghostly return of taxidermy during the colonial era permeated daily life like an uncanny genealogy of disjointed modernity. If we can posit the taxidermy of Chosŏn tigers with Walter Benjamin’s philosophy on the repetition of cultural history then how do the stuffed animals manage to contain the possibility of the reproduction of time, in the sense of the afterlife of colonial modernity in Korea? Susan Buck-Morss (1991, p. 369) elaborates on this when she illustrates Benjamin’s fascination with a female wax figure, quoting him as saying: “her ephemeral act is frozen in time.”1 Taxidermied tigers are unchanging, defying organic decay, and constantly querying acts of crepuscular remembrance. The Chosŏn tigers as taxidermy of the nonhuman diaspora are now the cultural embodiment of a particular historical moment.

In this essay, I wish to examine two or three Chosŏn tigers in cartographic images, photography, and literature as the chronotope of the continual coloniality of Korea. As the tigers now roar silently in museums, or exist in modes of animistic traditional fables, appear in moralistic shorts as personified figures, their scaffold nonetheless is their primordiality of the modern against the compressed modernity of Korean society. Tigers preserved as taxidermic time, that is, the spatio-temporality intentionally excluded, sanitized, and colonized from the anthropocentric concept of the modern—what we might call the sphere of negativity—in the déjà vu future yet to arrive. Starting from this most peculiar, melancholic, and mutually contradictory premise, I wish to make a historical conjecture as to the tropes of the tigers’ inextricable binds to the trajectory of the knowledge structure in this realm of the present-past: continual coloniality.

Gilles Deleuze explains the paradox of contemporaneity by pointing out that the past is the apriori precondition on which the present is founded.2 In other words, it is only when the present and the past exist in the singular and in the same frame of time that time can flow wholly for the present. However, not all pasts are latent in the present since there is a past—an animal past—that has never been part of the present as a form of pure past. Following Deleuze’s argument my question is, to what category of past does the era of the pre-modern and primitiveness, as in the time of the tiger, belong, which we all believed died within us in the era of modernity? To what category does primordiality, as the pure past, belong in the sphere of postmodernity—if that is indeed what we should call the present?

In the Chosŏn dynasty, tigers were portrayed ambiguously as both benevolent and malicious in the early cultural texts of Korea’s pre-modern period. The tiger was worshipped as the shamanistic envoy of the mountain spirit (San-sin), the most revered deity of Korean animism as the nemesis of evil and protector of the virtuous. For example, talismans and protective paintings against the devil on residential gates prominently featured depictions of tigers. At the same time, there are various Korean folk idioms such as “a day-old dog does not even know the fear of a tiger,” expressing the horror the ferocious tiger engendered. During the Chosŏn dynasty, numerous systematic tiger-extermination projects were implemented, as tigers were designated Hohwan (lit. tiger disaster, 虎患), and a bounty system and special battalions of Ch’akhokapsa (tiger-hunting soldiers) was established. According to Joseph Seeley and Aaron Skabelund (2015) and Kim Dong-Jin (2017), due to the systematic campaign of tiger hunting, the tiger population, along with tiger attacks, seems to have decreased enough to preserve the species from the normal rate of hunting.

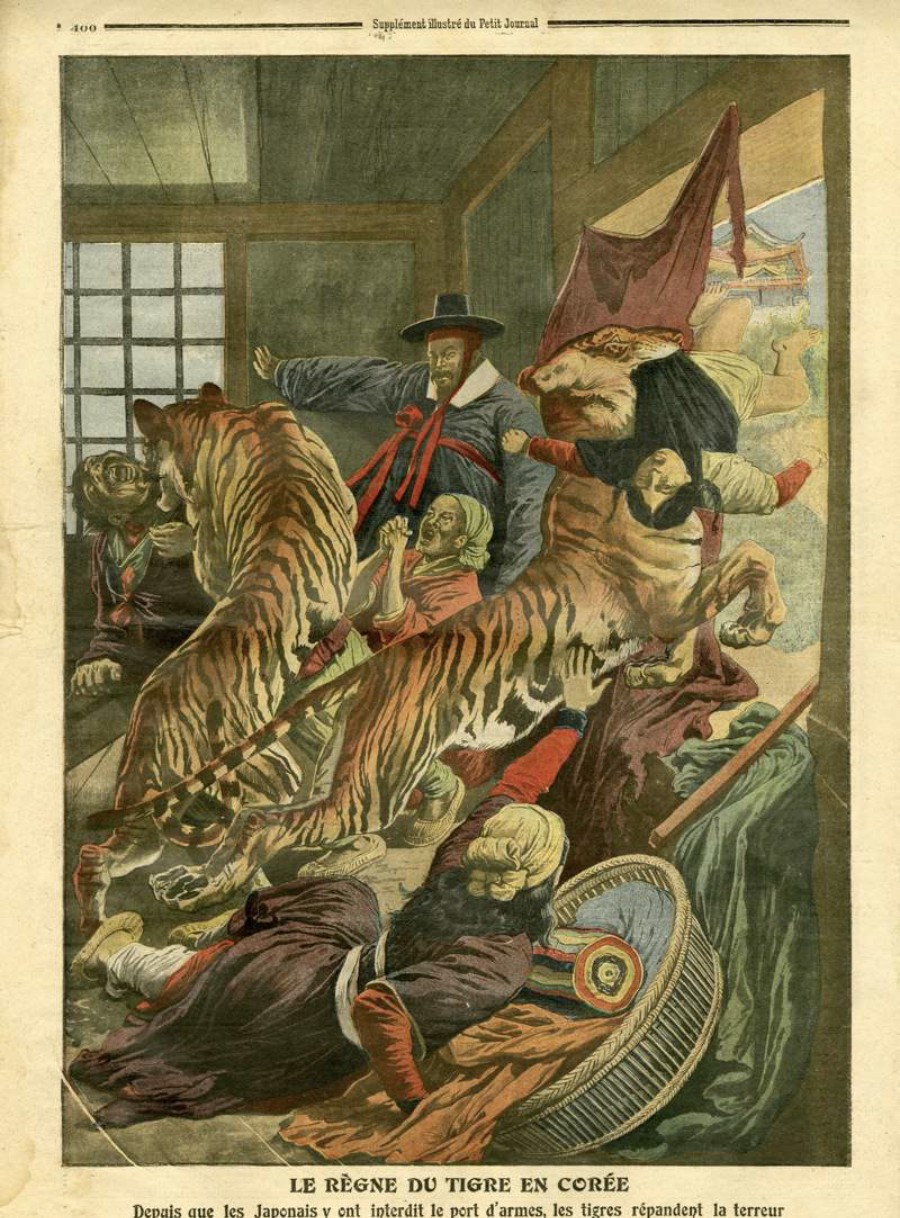

Le Règne du Tigre, 1909: Two Korean tigers attack a household, from an article in the French newspaper Le Petit Journal. The caption reads: “Tigers Reign in Korea: Terror spread by tigers since the Japanese prohibition on arms bearing.” According to the article, the Japanese were to blame for the tiger attacks on the defenseless Korean people.

If we could postulate the resurrection of the tiger as an ontological issue preceding the topos of translating the pre-modern to colonial Korea, how might we utilize the academic disciplines of the humanities to decipher the links between such symptoms and affects from the pre-modern past that has never been part of the present? Giorgio Agamben argues in The Open: Man and Animal (2004) that humans have always contemplated the incomprehensible zygote of the supernatural, social, and sacred elements through natural organisms, and for that reason, have learned to contemplate human essence in accordance with the difference between humanity and animality. In other words, Agamben argues that the variously derived epistemological “differences,” designed to separate humans from animals/nature, were possible ultimately only because of the strategically molded “anthropological machine of the moderns” that Otherized animals.3 Humanity as we know it today has been built up from such invention of anthropocentric differences, which is the state of the indecent caesura that tries to place humans above animals and nature in a hierarchical order and articulation. This human/animal hierarchy was already structured—looking at tigers ambivalently as both shamanistic spiritual guardian symbolically, and the menace of agrarian economy physically—during the Chosŏn dynasty.

As Martin Heidegger would put it, it is a state in which animality cannot but be placed beyond the boundary of human openness toward the world (or contemplation in the form of l’aperto).4 Now, the discourses on animals and nature, permanently Otherized in the narrative structure of modern history, are being reinstated; they are the reverse, or hidden side of modernity, always considered irrational, the “Other,” and negative, as represented by nonhuman animals.

For example, in the Animism exhibition project, curator Anselm Franke embraces the Derridian hauntology of modern visual and intellectual history as a curatorial methodology, which could not but be placed in a state of vacuum in the narrative of a history. Franke embraces the spectral history of the modern knowledge system of the Other as part of an animal/animistic discourse and actively re-invokes the names that fall under animism. By doing this, he raises a flag of objection against the basic human-centric discursive frameworks supporting the systems of modern museums and schools and immigration and mental health policies as well as a scientific epistemology based on animal experimentation. All these were systems established under the aegis of modern sociocultural anthropology, which itself was greatly influenced by the works of Franz Boas,5 who in turn believed in the progress of language and technology and the evolution of social forms. Potentiality, as an apriori condition and animism as a pure memory are strange bedfellows in modernity; in this sense, Franke suggests that a symbiosis of these mutually alien states is possible through their co-habitation and contact with one another. In making such a suggestion, Franke indirectly delivers a metanarrative and a genealogy of the symbolic system of the Western modern knowledge system through a re-enactment of animism.6 It is hoped that the discourses on animals, plants, and nonhuman hyphenated subjectivities—which have always existed, but which have been suppressed and hidden—will now gradually bring about a rupture in the dominant political topography of hierarchy, restore the warm and smooth texture of its original organic state, and freely cross the boundaries of various spheres.

The question now is who warrants the subjectivity of the nonhumans that Franke wishes to reinstate? Are the emotions, languages, and knowledge systems of the nonhumans always binomially opposed to those of the humans? What if the history of modernity is a narrative built upon a joint silence about the age-old discourse called animism/animality? And what if the current state of the narrative‒imaginative vacuum is the direct result of such collective silence among us all? Franke’s (2013) answer to these questions is as follows:

This silence [of modernity] tells us that it is actually not animism, but modernity that is the ghost—halfway between presence and absence, life and death. And the future grand narratives of modernity may well speak of this ghost from the perspective of its other, from its “animist” side.

If the metonymy of the interregnum, which Gramsci describes as an intermediate state between life and death, could be exchanged with Franke’s notion of “animism” as equivalents, we can find a series of visual representations from the art world7 as well as from the sphere of mass media and popular culture.8 The problem lies in the philosophical conundrum that “animism” has created in the spheres of epistemology and ontology, outside of the permissible visual representation system. In a similar manner of argument, the French philosopher Gilbert Simondon (1924‒89) discussed the boundary between animals and humans from the perspective of ontogenesis.9 With the concept of individuation, he avoids artificially distinguishing humans from animals. Instead, by questioning “Who/What will come after the subject,” he explored the subjectivity of the human/nonhuman.10 In his book Two Lessons on Animal and Man (2012, p. 62), Simondon individuated individuals from the dualistic hypothesis of man and animal, which is deeply entrenched in all major fields of the Western knowledge system. Thus, he rejects the thesis of the dualism of Cartesianism, which claims that only humans are res cogitans (“a thinking thing”) with a soul, and that all things without a soul, such as animals, are res extensa (an “extended thing”). Instead, Simondon argues that the continuity between human and animal will produce results: “what we discover at the level of instinctive life, maturation, behavioral development in animal reality, allows us also to think in terms of human reality, up to and including social reality which in part is made up of animal groupings and allows us to think about a certain type of relations, such as the relation of ascendancy‒superiority, in the human species.” This is because, ultimately, even the Cartesian humanistic subject cannot escape the vital signs of life, nature’s gift of the biosphere.

In the context of Korean modernity, the crucial aspect of the interstitial return of the primitive tropes, or the tiger as the chronotope of continual coloniality, is precisely that it is a reification of multilayered modernities that makes fissures in such a cognitive topography of the modern. Animism, or a return to the primordial, is a sign of the revolt against falling into embodied habitual thinking, a defense of anti-rationalism, and a fundamental questioning of the demarcation of normalcy and abnormalcy. As such, it tacitly recognizes, at the discursive level, nonhuman subjects (animals, plants, and inanimate objects) as subjective individuals. Accordingly, animism wreaks havoc on the existing topography of hierarchy maintained by humanity, causing social chaos and collective hysteria. In other words, the return of the primordial and/or tiger as the chronotope of continual coloniality in Korea, threatens the status reserved exclusively for humanity, which makes the colonial superior vis-a-vis nature; furthermore, it now opens up the possibility that Otherization and objectification of humanity is negotiable.

Accordingly, the premise of exploring animism symbolizes inevitably the possibility of losing our comfortable sense of contemporaneity and of the implosion of modern humanist thought which had endlessly Otherized and hyphenated the nonhuman and the non-living. The new order of borderlines and the foundation for logic de-contextualize the non-spontaneous cultural borders that exist between individuals and the world, and become the subversive substructure for overthrowing the false monopoly of the human-centered notion of subjective recognition.11

“Tigers are probably more numerous in the north than in the southern part of Korea, but from my own experience, confirmed by that of other British sportsmen and travelers, it is a much more difficult matter to find one there than in the south. […] My own most successful hunts have been in the island of Chindo, some thirty miles as the crow flies south-east of the open port of Mokpo, situated at the south-west corner of Korea.”

—Ford G. Barclay, “The Manchurian Tiger” (1915)

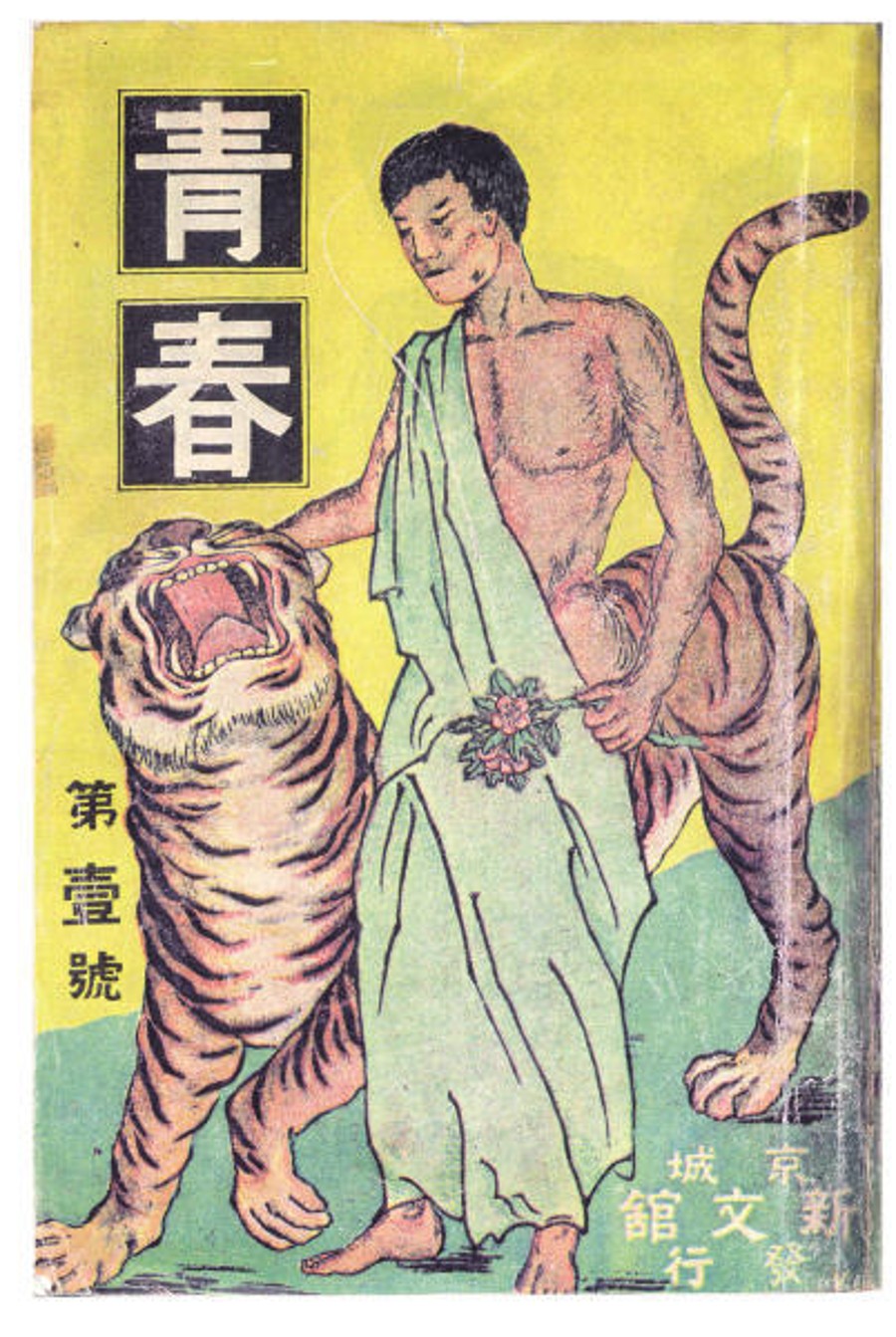

The modern concept of the tiger as chronotope started from a reimagining of the Korean Peninsula in the shape of a tiger. The modern Korean intellectual, Choe Nam-seon (1890‒1957) initiated a geographical project, whereby Korean territory was zoomorphically mapped out in the archetypal image of the tiger as a way of symbolizing independent Chosŏn. The first zoomorphic tiger map by Choe Nam-seon appeared in the first issue of Sonyeon magazine in 1908. The tiger image was further utilized as symbol of the nation-state in “Studying geography by Bongiri” (鳳吉伊) published in the first edition of the magazine Youth (Ch’eong-ch’un) in 1914. He added a further description about the cover painting where he explained that by drawing Korea as a tiger symbollically, he wished to express the country’s infinite development and the unfathomable nature of the Korean progressive spirit. The main trope of Choe’s geographic and symbolic reinterpretation of the Korean Peninsula through zoomorphic mapping, was in the juxtaposition of the shamanistic recuperation of traditional Korean spirits and identification with the country’s most familiar, yet territorial and apex predator, the tiger, as a national allegory, as he proclaimed the Korean Peninsula “the brave roaring tiger clawing against the Asian continent.”12

Geunyeokkangsanmaenghokisangdo (근역강산맹호기상도, 槿域江山猛虎氣象圖), late nineteenth- to early twentieth century, 46 × 80.3 cm, courtesy of the Korea University Museum; and Choe Nam-seon’s zoomorphic tiger map in Sonyeon magazine (November 1908).

In the early form of nationalistic representation of Chosŏn territoriality as the tiger, colonial subjects in Chosŏn/colonial Korea re-imagined their own sovereignty and vernacular territoriality as a means of reterritorialization through zoomorphic mapping in contrast to Japanese imperialism. This went against the Japanese geologist, Goto Bunjiro’s (小藤文次郞) drawing of Chosŏn in rabbit form, which defended Japanese Manchurian territory in 1903. The nationalist Choe Nam-seon, as a founder of Sonyeon magazine in 1908, utilized the imaginary topography of colonial Korea in the form of a vigilant tiger, used as a colonial tactic of psychogeography against Japanese imperialism.

Tiger and a young boy on the cover of the magazine Youth (Ch’eong-ch’un), 1914.

The tiger is seen as a symbolic totem of colonial Korean nationalism.

Choe’s tiger map was deeply embroidered on the heart of Koreans under Japanese occupation. However, in the midst of the cultural formation of the modern nation-state of colonial Korea under Japanese rule, geographical imagination and the modern concept of self and other gave way to a new sense of a modern order and transformative self-invention among Koreans. During the period of Japanese occupation, anthropology as an imperial discipline and popular tropes began to unconsciously internalize the contradictions inherent in the discourse of self and other among Koreans; furthermore, it propagated various models of the Asian Other, playing them against each other and encouraging competition between the colonies. At the same time, anthropologists, such as Torii Ryuzo of Japan, secured self-identity as the superior Asian who was “almost white but not quite,” while internalizing the Orientalist gaze overlaid on top of the colonized other (Lee 2017). Through various discourses on race, gender, and pseudo-scientific discourse, Imperial Japan maintained its self-identity and reorganized Asian’s epistemological topography with the logics of exclusion/inclusion and inferiority/superiority. The superiority of the Japanese “self” was thus secured by emphasizing the nonhumanity, the inferiority, and the logic of exclusion and inferiority against the Korean other. Thus, the academic disciplines of ethnology and anthropology laid the ideological foundation of the empire and its biopolitics; they inculcated in the colonized Korean a sense of self as a secondary citizen of the Japanese Empire; they were the ambivalent mechanism through which the body and mind of the Asian race were mobilized.

In the midst of these discursive formations, Choe tried to represent homogeneous and territorial sovereignty by reimagining the Korean Peninsula under Japanese occupation as a tiger, through the medium of zoomorphic tiger geography and serial publication of printed media. Thogchai Winichakul’s concept of the geo-body focuses on the role of modern maps, the visual and epistemological demarcation of people, and generation of a national consciousness, concerning not only the territoriality of the nation but also the geographic image of the nation itself as “a source of pride, loyalty, love, passion, bias, hatred, reason, unreason” (Thongchai 1994, p. 17). However, the relationship between the nationalistic zoomorphic imagery of the tiger and its allegorical narrative of Japanese anthropological perception to Koreans; and the urban reformation of the Korean Peninsula that followed, as well as the mass extermination of the tiger as a national symbol through trophy hunting, created a contradictive circumstance for the Korean people. As a consequence of Japanese urban reformation of the colonial metropolis in the name of modernization, the colonial metropolis, Kyŏngsŏng, began to lose its natural landscape through urban transformation. The result of this shift was that the dazzling transformation of the city’s downtown districts stimulated ordinary Koreans’ desire for modernization.

In this sense, the psycho-geographic structure of the colonial environment gradually influenced individual consciousness, since newly introduced modern concepts of time and speed in Korea regulated and domesticated the everyday lives of colonial urban dwellers. The complex experiences of these urban colonial subjects were tied to ambivalent sentiments, located not only in their recognition of being a part of the imperial body, but also situated in their hazy awareness of national identity caused by the internalization of their colonial circumstances. Raymond Williams argued that the modern metropolis acts as an intersection point in the experience of imperialism, saying, “This development had much to do with imperialism: with the magnetic concentration of wealth and power in imperial capitalism and the simultaneous cosmopolitanism access to a wide variety of subordinate cultures” (1989, p. 44). The discursive terrain of the Korean intelligentsia, which was gradually proselytized from a nationalistic patriotic podium praising colonial modern capitalism and validating the discourses of enlightenment and national consciousness through zoomorphic tiger imagery, faded after the late 1920s in the aftermath of the failure of the “independence movement.”

The tiger as powerful, independent, feared as a vicious killer, used as a primitive and nationalistic trope of benevolence and patriotism, pulls in Korean collective consciousness as double sutures both of symbolic terminations of sovereignty and national pride, and revealing the real ruptures from tradition. Various Western colonial trophy hunters and Japanese imperialists sought to elevate their status above the colonized through the hunting and display of countless slaughtered Korean tigers during the early twentieth century in Korea. Then there was a sudden shift in the tiger’s traditional, amiable, and valiant disposition in various fables, proverbs, and novella; this turned the creature into the maligned predator or harmful man-killing “varmint,” which threatened the progress of modernity, and must be massacred in order to accomplish the process of colonial modernization.

During the Japanese colonial period, tiger hunting, tiger-meat tasting, and tiger cubs kept in the houses of high-ranking Japanese officials became popular pastimes; and, for example, there was the sizeable 150-person tiger-hunting party organized by the wealthy businessman Yamamoto Tadasaburo. The party managed to slaughter three tigers. According to Seeley and Skabelund (2015), the physical and metaphorical killings of Korean tigers by the Japanese had strong imperialist connotations. This is because the ferocious tiger had been adopted as the symbol of Korea and Korean nationalism under Japanese rule: the independent nation and Korean ethnic identity were both symbolized by the tiger. The tiger was “the fiercest and strongest of all creatures,” and would nurture young Koreans into strong chigi (至氣, determined and spirited), was the hope expressed in an editorial article in Hwangsŏng sinmun (the Capital Gazette).13 The tiger became the embodiment of the pride of Korea.

Korean Tiger Hunting, 1922, photographed by Ando Kimio. According to the statistics of the Governor-General of Korea, the number of Chosŏn tigers slaughtered during the period of Japanese occupation was around 141. This tiger is arguably the last male tiger to have been photographed, on October 2, 1922, in Gyŏngju, Mt. Daedŏk, in Kyŏngsangbukto province. The tiger skin was dedicated to the Imperial House of Japan.

This chronotopic transformation of the allegorical tiger as a spiritual animal symbolizing nationalism into a malign predator threatening modernity was vividly portrayed in the Japanese intellectual and novelist, Nakajima Atsushi’s poetic novella, Tiger Hunting (虎狩, tora kari) of 1934. Regardless of Atsushi’s short literary career, his unique worldview during Japanese imperialism has been highly praised, partly because of his multilayered position as one of the colonizers having spent his youth in Kyŏngsŏng, Manchuria, and Palau. Based on personal experience, Nakajima Atsushi produced two novellas on everyday life in colonial Chosŏn—these were Tiger Hunting (1934) and The Landscape where the Japanese policeman is (1929). His unique observation of colonial life in Korea was markedly unlike that of other Japanese writers who supported the indoctrination of colonial cultural assimilation—naisen ittai (the ideology of Japan and Korea as a singular body). His primary motivation was to show how Korea had gradually become saturated and assimilated into the surveillance system of the Japanese imperialists, but his focus was on the self-deception of the colonized and the logical contradiction of naisen ittai and Japanese occupation of the colony, which he expressed through sharp criticism and detached sensibility.

Tiger Hunting is a story told in the first-person by a young Japanese man who has an unusual friendship with a colonial Korean classmate, Cho Dae-Hwan, a bourgeois Korean student who attends a Japanese school in Kyŏngsŏng. In the midst of the nihilistic saturation of sentiment in colonial Korea during the mid-1920s, “I” reflects the problematic Cho’s cynicism toward his Japanese classmates, “who don’t know anything about delicate modern aestheticism”; his unrealistic self-pride and condescending nihilism as one of the colonized toward the colonizer; and “I” also criticizes the contradictory Japanese assimilation policy in Korea. Cho’s apathetic nihilism forces the reader to appreciate the hopeless, emasculated dissatisfaction of the colonized men, which the many anecdotes of Nakajima Atsushi’s school years express, especially when Cho is severely beaten up by his Japanese classmates for his arrogant attitude even as one of the colonized. The “I” emphatically recollects the narrator’s sympathy for Cho who, crying, confesses that, “he could not resist them for fear”:

I was happy to know that Cho, who had been so sarcastic and proud of himself, showed his true-self as a naked, coward colonized—realizing the fact that he is not the naichijin (Japanese). That (difference between us) gave me satisfaction.14

While colonial masculinity-in-crisis is revealed in Cho’s scopophillic confession, “I” as colonizer recuperated the narrator’s own superior position as the colonizer, by observing the despair of the pompous colonized subject. Nakajima Atsushi’s literary text depicted the colonial reality of his own connection with the ideology of assimilation. This is expressed both in the contradictory reaction of the narrator’s Japanese father (“my father never liked me getting into a close relationship with Cho; while he was always preaching to me about how Japan and Korea should be unified under the same citizenship”) and in the reverse—colonialism within the colonized community while out tiger hunting. The narrator recalls Cho’s secret proposal to go on a tiger-hunting trip with Cho’s father and servants near Kyŏngsŏng. After a long wait, they see a tiger, which attempts to “play” with a Chosenjin (Korean) in the morning dust, but following three gun shots the tiger falls to the ground and “I” and Cho get to look closely at a real tiger for the first time. It is then that “I” is confronted with the bare life of the Korean:

What surprised me was Cho’s attitude at that time. He approached the servant man who was only stunned, and [Cho] fell down to confront the tiger, kicking his body saying “he wasn’t even hurt at all.” He was resentful to find that the servant was unharmed and there was no victim of the tragedy; he had been expecting to see a spectacle. […] Suddenly, I felt like I saw the blood of a powerful colonial family by watching Cho’s cruel and indifferent eyes.15

Cho’s primal fear as the colonized male is not related to fear for the tiger itself but to his damaged masculinity, as the allegory of the dead tiger as Korea’s lost sovereignty invigorated the embedded colonialism of his colonized mind. Cho’s ambivalence as both a cruel bourgeois master to his servant, and the inferior colonized as Chosenjin gave him a scopophobic anxiety (Cho eventually disappears after the tiger-hunting trip) in relation to the mobilization of the voyeuristic modes of spectacle of colonial modernity.

Since the liberation of Korea, such differentiation amounts to no more than the narrative of the ethnic abjection16 in which the West internalizes the meaning through relational networks of Others (Chow 2001). The differentiation is no more than the molding flasks of cultural capital, which shape desires devoid of any historical context. The question, then, is, in the East Asian context, after Japanese defeat and Korean liberation, how do the discourses of colonialism and pseudo-science remain as historical trauma among Koreans who remember colonialism? We have witnessed the internalized rhetoric of colonialism unselfconsciously uttered; the return of the narrative of the purported purity of Korean mono-ethnicity; and imitations of colonizers. How have these symptoms become embedded as scars and loss of memory among Koreans? And what do the signs of the return of the primordial say about Korean modernity after all?

The tendency of postwar-period South Korean society was for its representatives to take a diverse cultural approach that obsessively repeated the odd narrative of retrieving the Japanese colonial era by passing through “manic depressive” narratives of the joy of liberation and the anxiety of a divided country. The agenda for casting Japanese colonial history into oblivion by numerous Korean media culture was subsequently replaced quite smoothly with the nationalistic campaign of anti-communism and “the heyday of new liberation” by Syngman Rhee’s government, which recognized that any reference to the Japanese was culturally taboo. The undisguised grudges continued at the very interior of Korean national self-refashioning during the Jeju massacre of April 3, 1948, and the Korean War, along with the anti-communist ideology born through experiencing the division of a nation. The “Japanese” as the monstrous remnants that needed to be subjugated and removed from the official collective memories of Koreans by Syngman Rhee’s government and the U.S. Army, which attempted to utilize the suppressing apparatus, became a narrative of the media culture and formed its propaganda after liberation. Postcolonialism and Western modernization in South Korea, like a game of cross-and-pile have been structured on a base of contradictory modernism. The society, built on this unstable base, destabilized by the intentional loss of much of the colonial past, while searching for a pre-colonial past troped as “traditional”—a sentiment that pervades Korean society—tried to catch up with Western civilization, while distancing itself from the bitter memories that came with its occupation by Japan.

In December 1942 during the Asia‒Pacific War, the Japanese Empire ordered the decree of Elementary Schools via indoctrination of naisen ittai, the Japanese policy of assimilation. Under this decree, the existing Korean primary schools (known as “So hakgyo”) were changed into Japanese-style elementary schools where Chosŏn children were raised as potential fascist soldiers and were forced to worship at the Yasukuni shrine and swear an Oath of Imperial Japanese Citizenship. Reading the Japanese youth magazine Shounen Club and a manga called The Adventures of Dankichi, while dreaming of becoming fascist soldiers, Chosŏn children suddenly all turned into Lee Seung-bok.17 These anti-communist boys “hated communists,” and after liberation were raised as the fathers who featured in the conquering-the-monsters-of-the-North popular media stories, such as in the propaganda animations General Ttoli (1978) and The Adventure of Hamedori (1981). The majority of South Koreans did not get a chance to mourn their loss of sovereignty, their own absence of historical consciousness, or to forgive the “Other.” After liberation, basically, they settled for becoming the victims of the discursive frameworks generated through the tropes of Comfort Women (Japanese survivors of wartime sexual slavery) propagated by the Japanese government, the Korean War, and the division of the nation. In addition, their children—who recognized the North Koreans as horned devils or animals—participated in anti-communist oratorical speeches or propaganda poster contests, proliferating their own individual fascism among themselves. Most South Korean children commenced the school day by repeating the Charter of National Education with the phrase “In front of the proudly hoisted Taegeukgi,” and watching American animations by Disney and the seminal piece by Japanese Matsumoto Leiji, Galaxy Express 999. In fact, they have grown up in strikingly similar environments to the colonizers in their hybrid realities. They also experienced a strange sense of the nationalistic mission to destroy the “North Korean monsters” while proudly singing along to anti-communist propaganda songs, and at the same time delighting in the overwhelming emotions ambivalently triggered while watching General Ttoli as he defeats the North Korean Others, which are depicted as animals—the evil Red-pig leaders and wolves.

On the subject of the invasion of the North during the Cold War, this was played out according to the military dictator, Park Chung-hee’s agenda to detract social criticism during the Yushin regime. The anti-communist animation General Ttoli: The third underground tunnel (1978), was produced in lieu of the discovery of the underground tunnel constructed by the North, and clandestinely internalized a pastiche of the kids’ primitive heroic Hollywood story of Tarzan with an anti-communist narrative. While Tarzan—originally produced by Edgar Rice Burroughs—was vehemently criticized by American critics for its white supremacist, misogynistic, and racist undertones, the racist metaphor was unabashedly appropriated in General Ttoli. Monopolizing the white supremacist narrative, and at the same time boasting of its self-identifying greed for narcissistic sub-imperialism, the animation stigmatized the North with an animality that could not have been Otherized any further within the same species.18

The North Koreans represented as animals—e.g. rats, pigs, wolves, and foxes—now became the Other of South Koreans, and along with this collective hatred came the negative symbolism linked to various diseases with which animals might infect humans, such as mites, endemic typhus, epidemic hemorrhagic fever, and so on. In doing so, the anti-communist narrative as disseminated by the popular media became deeply embedded in the popular imagination; and, embedded within daily life it constituted the unique heterogeneous contemporaneity of the South Koreans, who led surprisingly similar lives to those of the empires after the liberation. Therefore, various class-, gender-, and ethnic-based narratives suddenly became sutured in a fabrication promoting the “modernization of the fatherland” and “all-out national security.”

The two biggest wars to break out following the rearrangement of postcolonial Asia into nation-states were the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Through participation in the Vietnam War as mimesis of Emperors (of the US and/or Japan) the South Koreans, sending their healthy sons and husbands to take part in the Asia‒Pacific War, repeated the recursive narrative of the Home Front woman sewing seninbari to support the Japanese Emperor. Similar to the necropolitical logic of Japanese intellectual discourses during the Asia‒Pacific War, the intervention of Park’s military government persuaded South Koreans to dispatch their husbands and sons as volunteer soldiers to the Vietnam jungle, to fight to revive South Korea’s capitalist system. Park’s government arranged to dispatch troops to Vietnam through ratification of a treaty called the “Brown Memorandum” for the sake of economic aid from the US. From 1965 to 1973, over 320,000 South Korean military soldiers were sent to Vietnam under the banner of the nation’s modernization (chokuk kundaehwa), indeed resulting in a major turning point for South Korea in terms of economic growth, majorly focused on the Chaebol—Korean conglomerates such as Hyundai, Daewoo, and Hanjin—which were given construction contracts in Vietnam.

This enabled Korean workers to find jobs in the abounding Vietnamese economy after the war. Mbembe (2003) describes necropolitics as the existential predicament of subalterns living in colonial and postcolonial regions, and Park’s regime shrewdly transposed the logic of economic modernization to the sovereign’s right to kill, while leaving the rest of the population in a state of living death. In 1968 the National Charter of Education (Kukmin Kyoyuk Hŏnchang), which began with the sentence “We are born in this land with the historical mission to regenerate our nation,” was to be memorized by every Korean and recited at the beginning of all official events in the army, prisons, schools, and factories. Mobilization of patriotism and mono-ethnic myths was invigorated by way of a major revision of history textbooks and ethical curricula focusing on the story of national heroes, allegorizing the heroic narratives into Park Chung-hee’s (Takagi Masao) military career as Imperial Japan’s lieutenant in the 8th Infantry Division of the Manchukuo Army.

In the wake of the dislocating traumas of the Korean War and the proletarianization of Koreans from the rural areas during the Vietnam War, the collective desire of Koreans toward compressed modernization found itself paralyzed by an enchantment with phantasmagorical modernity. This materiality was the imperial consequence of liberation, and eloquently conveyed a collective conjuration caught up in a simulacrum of admiration for modernization—in stark contrast to the reality of the situation. During the fast infiltration of the introduction of the modernization movement in South Korea during the mid-1960s, President Park Chung-hee provided an interesting conflation of forms of propaganda paralleled with images and news of the Vietnam War. By disseminating the spectacles of visual propaganda in the form of a sanitized form of violence and discourses of national solidarity, Park interpellated the nation into being by using the pronoun “we” for the sake of building the imagined community. By casting this national subject as a potential participant in the Vietnam War by using the address “we” and “us,” the televised visual apparatus embodied both the nation’s solidarity and its collective memory.

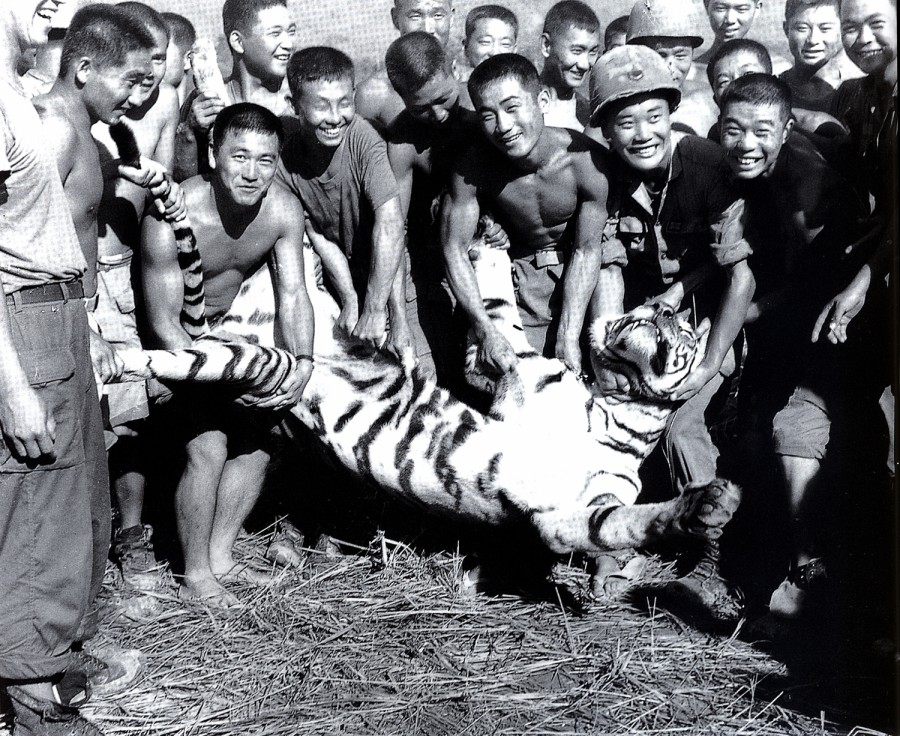

In the midst of the jungle in Vietnam where Korean soldiers disguised the massacre of numerous Vietnamese civilians as humanitarian aid, numerous photographs of tiger corpses killed by Korean soldiers were taken. Tigers, once symbolizing the national sovereignty of colonial Korea, were exhibited with their guts cut, slaughtered by war veterans of the Tiger Division. Metaphorically, this exposed the imaginary topography on which South Korea—with its internalization of colonial logic, and experience that mirrored the other Asian countries—consolidated its position as a sub-imperialist nation by dispatching soldiers to the Vietnam War, through an act of postcolonial mimicry.

Korean veterans Tiger-hunting during the Vietnam War, July 10, 1968. Photograph by Kang Jin Seung. Courtesy e-History channel, Korea TV (國民放送)

According to Claude Levi Strauss (1963, p. 180), the effect of the conjuration could depend on how much a member of the community was willing to accept the effect of the conjuration, rather than relying on the ability of the conjurer itself. The collective desire for modernization, and enchantment for the phantasmagoric materiality created by the imperialists after liberation, eloquently conveys how this collective conjuration, caught up in the simulacrum of admiration for modernization was far from the actuality. In this light, postwar South Korean society suppressed individuals’ desires, reinforced sacrifices, and mimicked the colonizer with a phallic capitalist victimizer’s mask through their voluntary alliance and participation in the war alongside the US. In so doing, during the process of constructing the modern state, state-controlled capitalism has unavoidably borne irrationality and madness. The irrational compressed modernization of Park Chung-hee reconstructed South Korean’s paradoxical identity as hermaphrodite—as both colonizer and colonized—by making others, Korean working-class soldiers dispatched to Vietnam, nurses sent to work in Germany, Yanggongju (sex workers) enslaved for the pleasure of American soldiers, female factory laborers, communists, and the whole Chŏllado province, scapegoats. We still silently turn the switch of trauma and fascism on and off within the “Other’s” unconsciousness, floating as specters in Lee Seung-bok’s anti-communist education agenda and Park Chung-hee’s modernization process.

The body of South Korea has experienced rhetorical plagues with the enchanting but humiliating ambivalence between discourses of victimhood and colonial modernity, the conjuration named anti-communism and fascism, the invention of the North Koreans as the “Other,” and ethnocentrism, and compressed modernization during the twentieth century. The rhetorical plagues as metaphors have prompted collective fear by enunciating the survival of the nation-state, and through propagating disastrous representations implying the apocalypse, and world crises. In addition, the rhetorical plagues also had the tendency to neglect and deny the reality by identifying mercy and tolerance with self-indulgence and indecisiveness, confusing and corrupting manners using paranoid and schizophrenic rhetoric. In this light, the representation and return of trauma shown in the landscapes of reality and the media hover across the threshold between the non-modern and the modern through the logic of sorcery and Protestantism, the rhetoric of anti-communism and nationalism, with multiple layers of improvisations on colonial history. The prosthetic modernity embedded within the colonial memory from the two emperors, Japan and the US, caused a postcolonial pathology in which the South Koreans incessantly imitate the empires, while underestimating themselves and thereby limiting their own possibilities.

“What had to remain in the collective unconscious as a monstrous hybrid of human and animal, divided between the forest and the city—the werewolf—is, therefore, in its origin the figure of the man who has been banned from the city. […] It is a threshold of indistinction and of passage between animal and man, physis and nomos, exclusion and inclusion: the life of the bandit is the life of the loup garou, the werewolf, who is precisely neither man nor beast, and who dwells paradoxically within both while belonging to neither.”

—Giorgio Agamben, “The Ban and the Wolf” (1998, p. 105)

In discourses of modernity, the “repatriation” of animals as the chronotope of colonial modernity has been handled as if the subject was an appendage. We have been through the stories of the disgraced scientist Hwang Woo-suk and the first cloned wolves from Seoul National University; the endless questions about stem-cell research and life science technologies; in addition, there are also Mark Rowlands’ juxtaposition of his pet wolf and Freud’s wolf man patient; Dominick LaCapra’s discussion of animal‒human boundaries; and Jane Goodall’s emphatic talk of the “more human than human” Bonobo chimpanzees. How far is the limit of the ambiguous ethical questions about humanity? The logic of species was started by Darwin; the Japanese philosopher of science Tanabe Hajime of the Kyoto School gave that a slight twist to promote his logic of ethnically homogeneous modern nation-states and to promote his logic of race (minzoku), in order to embrace the notion of the racial superiority of Japan, the imperial mediator. What are the Lamarckian legacies implanted in our bodies by the Western imperial philosophical discourses that relentlessly Otherized multinational races and families, genome and individual, and homosexuals and people of color in order to obtain holistic humanity? What could ultimately remain as the human? In this essay, the question I ask is why are the animals/tigers trying to come back as the chronotope of continual coloniality? The tigers, “neither human nor beast,” nevertheless lived among us, but then were ostracized from us.19 They are now trying to come back through animism, through the return of the have-lived, in postcolonial Korea.

I have tried to answer this question indirectly by reviewing the genealogy of discourses on tigers and colonial men in various intellectual history and media forms, which have fissured and ruptured modernity. Imagine a tiger or other animal striding back right through the modern and blurring the boundaries. This essay must conclude with a discussion of how the return of the dispossessed, its dreadful prospects, and our screen memories of animality can be transformed and become curative memory. Taking an anti-dualistic position, I have tried to explain the logics and tropes of the primitive; that is to say, I wish to be on guard against humanist reflections of pseudo-postcolonial narcissism. I wish to posit from the opposite position to expose that animism/animality became the Deleuzian pure past only after a long period of inactivity as a reflection of animalistic humanity, defined as irrational and anti-scientific by modernity, and then ultimately born dead from it. From animal motifs in mythology to animal images in pulp fiction and popular culture—for example a North Korean animal speaking Korean in an anti-communist propaganda animation; the human-like taxidermied animals in Abel Abdessemed’s unorthodox work Who’s afraid of the big bad wolf; and the therianthropic characters in the Korean fantasy film A Werewolf Boy (2012) and in the Japanese anime Wolf Children Ame and Yuki (2012); repatriating the last Chosŏn tigers on the screen with CGI in the Korean-made The Tiger: An Old Hunter’s Tale (2015)—the reification of animals has appeared gradually as familiar “Others” vis-à-vis the modern. As such, the animal has been read as symptomatic of collective unconscious, as metaphors for the performative self and monstrosity, which were absent in the discourses of modernity. These readings of animality are the modern versions of the Renaissance-era “cabinets of curiosities.”

If such readings are triggered by ecological clichés stemming from collective feelings of guilt and pity caused by the expansion of civilization, the reduction of bio- and species-diversity, and the extinction of wildlife, I would like to claim an alternative. Instead of the guilt and pity my claim is that animals and images of them have never been completely extinguished, so that their absence should never again be caught up in the dichotomies of the internal/external, culture/nature, and natural object/cultural subject. Animism has always co-existed within us in the form of co-figuration, residing in our unconscious and hovering around in the vicinities of our neighborhoods. It lives as a metaphor for discourse on gender-hierarchy; as scientific-technological meta-databases, such as genes, seeds, embryos, and DNA; and as the mechanism for ethnic- gender- and racial-discrimination. Now it has even evolved into a high-tech-obsessed erotogenic totem version of Tamagotchi, a hand-held digital pet toy and Pokemon Go in augmented reality. Accordingly, I do not wish to make a hasty conclusion about a utopian future for animism/animality by defining it as an extended concept of ethnicity or kinship, or as a passive kinship relation where humans have always been part of nature. That is because solidarity based on kinship and genes and homogeneity always produces new exceptionalities with their logic of exclusion and inclusion.

Only when we resist the temptation of classification (perish the thought of actually being able to objectify nature) and go beyond making boundaries of exclusions and inclusions will we arrive at the sphere of the holistic subject, guided by the unfamiliarity of the heterogeneous narrative that is nature. When we undo the restrictive spells of the collective colonial narrative, shaped by complacent humanistic strategies and the intellectual, aesthetic, archival desires of Western intellectual history, we should then be able to decipher once again the subversive scenarios that crisscross life-and-death boundaries, told by the aimlessly wandering ghosts of the netherworld, by the unfamiliar and bizarre affects of nonhumanity, and by the bodies and souls that originally belonged to shamanism and animism, which cut across the “boundaries” of pre-modern and modern.

References

Agamben, Giorgio, “Ban and the Wolf,” in Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller Roazen. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Agamben, Giorgio, The Open: Man and Animal. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004.

Barclay, Ford G. et al., “The Machurian Tiger,” in The Big Game of Asia and North America: The Gun at Home and Abroad, Volume 4. London: London & Counties Press Association, 1915.

Buck-Morss, Susan, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

Chow, Rey, “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection,” Traces 2: A Multilingual Journal of Cultural Theory and Translation, Specters of the West and Politics of Translation (2001), pp. 53‒77.

Deleuze, Giles, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul R. Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Franke, Anselm, “Animism: Common Ground and Historical Difference: Thinking about the Framing Narratives of Culture,” in Savage Garden of Knowledge: Asian Potential for the New Society. Gwangju: Asian Culture Complex International Conference, 2013.

Gramsci, Antonio, Selections from the Prison Notebooks. New York: International Publishers, 1971.

Green, Susie, Tiger. London: Reaktion Books, 2006.

Kim, Dong-Jin, Chosŏnŭi Saengt'aehwan'gyŏngsa (History of Chosŏn ecology). Seoul: P'urŭnyŏksa publishers, 2017.

Lee, Yongwoo, “The Return of the Have-Lived: The Non-Human, the Animal and the Ever-present memory in Postcolonial Korea,” e-flux, Superhumanity: e-flux, architecture (2017). Advance publication [online]

Levi-Strauss, Claude, The Sorcerer and His Magic, in Structural Anthropology. New York: Basic Books, 1963.

Mbembe, Achille, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture, vol. 15, no. 1 (2003), pp. 11–40.

Nakajima Atsushi, Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, and Katsuei Yuasa, Sikminchi chosŏnŭi p'ungkyŏng, trans. Choi Kwan & Yoo Jae Jin, Tiger Hunting. Seoul: Korea University Press, 2007.

Sakai, Naoki, “Ethnicity and Species: On the philosophy of the multi ethnic state in Japanese Imperialism,” Radical Philosophy, vol. 95 (May‒June 1999), pp. 33‒45.

Seeley, Joseph, and Aaron Skabelund, “Tigers—Real and Imagined—in Korea’s Physical and Cultural Landscape,” Environmental History, vol. 20, no. 3 (2015), pp. 475‒502.

Simondon, Gilbert, Two Lessons on Animal and Man, trans. Drew S. Burk. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Taylor, Mary Linley, The Tiger’s Claw: The life-story of East Asia’s Mighty Hunter. London: Burke, 1956.

Williams, Raymond, The Politics of Modernism. London: Verso, 1989.

Winichakul, Thongchai, Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1994.

Buck-Morss describes the wax figure in the Musée Gravin as a “Wish Image as Ruin: Eternal Fleetingness,” and that “No form of eternalizing is so startling as that of the ephemeral and the fashionable forms which the wax figure cabinets preserve for us. And whoever has once seen them must, like André Breton (Nadja, 1928), lose his heart to the female form in the Musée Gravin who adjusts her stocking garter in the corner of the loge.”

Deleuze says “what we call the empirical character of the presents which make us up is constituted by the relations of succession and simultaneity between them, their relations of contiguity, causality, resemblance and even opposition. […] what we live empirically as a succession of different presents from the point of view of active synthesis is also the ever-increasing coexistence of levels of the past within passive synthesis.” Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul R. Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 83.

Agamben wrote, “Insofar as the production of man through the opposition man/animal, human/inhuman, is at stake here, the machine necessarily functions by means of an exclusion and an inclusion. […] We have the anthropological machine of the moderns.” Giorgio Agamben, The Open: Man and Animal. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 37.

The “openness” or “world openness” that Heidegger advocates in Being and Time starts with cognitive behavior, in that all human behaviors are always, already (immer, schon) preconditioned. It starts from the premise that within the human ontological frame of “being-in-the-world,” i.e. within the premise that is completed apriori, all relationships formed by “is-ness” (seiendes), including cognitive behaviors, are open. Accordingly, all is-ness already receives its presentness and significance from its openness. According to Agamben, the externality of animality is the point where animal or physis is deprived of the significance of its presentness, and where its independence and autogenesis are dislocated—or in a Heideggerian term “de-worlded” (Entseltlichung)—by humans. The physis (nature) de-worlded through projection of human opportunity cannot but be placed within the scope of the order and hierarchy already created by humans.

Franz Boas (1858‒1942) was a German-American anthropologist who has been called the “Father of American Anthropology.” His research covered the areas of physical anthropology, linguistics, and ethnology, and in particular focused on Native American Indians. He is credited with having laid down the methodological foundation that is still used by anthropologists today to classify cultural forms and further advance the study.

The nature of the boundary between humans and animals, or between humans and nature, has been an endless subject of controversy in the Western philosophical tradition. Assemblage (2010) and Life of Particles (2012) by Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato were both written to commemorate the artists’ friendship with Félix Guattari (1930‒92). In these works, they explore ways to break down modern boundaries between nature and the human, dealing with the subject‒object issues framed within the topic of “tentative and essential return” through reinstatement of the animist conception of subjectivity, the subject on which Guattari worked passionately. Melitopoulos and Lazzarato argue that subjectivity is a superstition and advise that humanity move away from subject-centeredness; they further argue that the return of animism is not a return to irrationalism, that humanity should reinstate the subjectivity of animism as a natural state that is manifested multiple-simultaneously and unconsciously, through indeterminate forms of assemblages, such as individual entities and space, and architectural structures and affectless objects.

Examples include the following works shown as part of the Animism exhibition: the slide works of Marcel Broodthalers, the animal assembly painted by an unknown Ethiopian artist, and León Ferrari’s iconography of the dichotomy between animals and humans.

Works include, for example, animated productions by the Walt Disney Company to Isao Takahata’s Pom Poko (1994) and the neo-animist paradigm of Hayao Miyazaki, such as Princess Mononoke (1997). Thus, the animism discourse continued quite naturally through the symbolic discourses that are already very familiar to us.

Ontogenesis refers to a process of an embryo, or an egg fertilized by parthenogenesis—in other words an asexual embryo and spore—forming in an adult.

The Animism exhibit best matched to Simondon’s individuation theory is probably that by Daria Martin, titled Soft Materials (2004). In this work, she shows prosthetic body parts as machines that operate as metaphoric replacements for the human body. Martin thus explores the labor exchange-value between body and machine, and the mutually complementary articulation and pair-exchangeability between human and machine.

For example, The Love Life of the Octopus (1965), one in the series of twenty-three films entitled “Science is Fiction” by Jean Painlevé, or the “Nonhuman Rights” works by the Brazilian-born architect Paulo Tavares. These show intimate details of the intellectual capacities of the nonhumanity, or animality; the emotional expressions; cooperation among nonhuman life forms; and furthermore, the legal fights to secure equal legal and ethical rights based on the commonalities between the human and nonhuman. Works such as these are reflections of the pride and prejudice of the dichotomy between subject and object, and between nature and human, introduced by modernity.

On the cover of the first youth magazine in Korea, Red Chogori (붉은 저고리), there was the picture of a boy shaking hands with two tigers. The Youth, launched in 1914, also depicted a tiger whose head was being stroked by a young man.

“Chido ŭi kwannyŏm” [The concept of maps], Hwangsŏng Sinmun, December 11, 1908.

This translation and emphases in bold italics by the author. Atsushi Nakajima, Sikminchi chosŏnŭi p'ungkyŏng; trans. Kwan Choi and Jae Jin Yoo, Tiger Hunting. Seoul: Korea University Press, 2007, p. 47.

See pp. 66‒7 of Atsushi Nakajima, Sikminchi chosŏnŭi p'ungkyŏng; trans. Kwan Choi and Jae Jin Yoo, Tiger Hunting. Seoul: Korea University Press, 2007. This translation and emphases in bold italics by the author.

The term “ethnic abjection” was first used by Rey Chow in “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection.” Postcolonial theories have contributed to the global spread of the discourse of hybridity and cultural diversity as counter narratives to transnationalism and globalization. “Ethnic abjection” refers to the identity of heterogeneity that is being artfully concealed within this counterdiscursive frame and the emotional structure of the ambiguity, rage, pain, and melancholy brought about by the politics of recognition.

Lee Seung-bok was a nine-year-old South Korean boy brutally murdered by North Korean commandos in December 1968. The case of his murder was widely publicized throughout South Korea during the Park Chung-hee dictatorship. In the early 1990s, however, it was claimed by historians that his death was the creation of anti-communist propaganda since Lee had never existed.

Sakai’s critique (1999) on the myth of mono-ethnicity and the conceptualization of species within the domain of nation-states against Tanabe Hajime’s logic of species and the binary tropes of Nihonjinron challenged the particularism of postwar Japanese mono-ethnic nationalism while asserting ambivalent accountability of the particular and the universal. Sakai claims that the ambiguity of the logic of the Kyoto School scholars is entrapped within empirical terms such as race, ethnos, nation, folk, or the terms of Tanabe’s “species” (shu) and “genus” (ryu). This eventually exposes nationalism’s logical instability and its inability to conceptualize ethnicity/nationality of the particular/universal within the historically determined, therefore endlessly indeterminate categorization; and thus it is a dialectical process based upon individual negativity and facticity.

The wolves symbolize a metonym of the return of the primitive in the collective unconscious, as what Agamben (1998, p. 105) describes as “a monstrous hybrid of human and animal.”

1. Buck-Morss describes the wax figure in the Musée Gravin as a “Wish Image as Ruin: Eternal Fleetingness,” and that “No form of eternalizing is so startling as that of the ephemeral and the fashionable forms which the wax figure cabinets preserve for us. And whoever has once seen them must, like André Breton (Nadja, 1928), lose his heart to the female form in the Musée Gravin who adjusts her stocking garter in the corner of the loge.”

2. Deleuze says “what we call the empirical character of the presents which make us up is constituted by the relations of succession and simultaneity between them, their relations of contiguity, causality, resemblance and even opposition. […] what we live empirically as a succession of different presents from the point of view of active synthesis is also the ever-increasing coexistence of levels of the past within passive synthesis.” Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul R. Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 83.

3. Agamben wrote, “Insofar as the production of man through the opposition man/animal, human/inhuman, is at stake here, the machine necessarily functions by means of an exclusion and an inclusion. […] We have the anthropological machine of the moderns.” Giorgio Agamben, The Open: Man and Animal. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 37.

4. The “openness” or “world openness” that Heidegger advocates in Being and Time starts with cognitive behavior, in that all human behaviors are always, already (immer, schon) preconditioned. It starts from the premise that within the human ontological frame of “being-in-the-world,” i.e. within the premise that is completed apriori, all relationships formed by “is-ness” (seiendes), including cognitive behaviors, are open. Accordingly, all is-ness already receives its presentness and significance from its openness. According to Agamben, the externality of animality is the point where animal or physis is deprived of the significance of its presentness, and where its independence and autogenesis are dislocated—or in a Heideggerian term “de-worlded” (Entseltlichung)—by humans. The physis (nature) de-worlded through projection of human opportunity cannot but be placed within the scope of the order and hierarchy already created by humans.

5. Franz Boas (1858‒1942) was a German-American anthropologist who has been called the “Father of American Anthropology.” His research covered the areas of physical anthropology, linguistics, and ethnology, and in particular focused on Native American Indians. He is credited with having laid down the methodological foundation that is still used by anthropologists today to classify cultural forms and further advance the study.

6. The nature of the boundary between humans and animals, or between humans and nature, has been an endless subject of controversy in the Western philosophical tradition. Assemblage (2010) and Life of Particles (2012) by Angela Melitopoulos and Maurizio Lazzarato were both written to commemorate the artists’ friendship with Félix Guattari (1930‒92). In these works, they explore ways to break down modern boundaries between nature and the human, dealing with the subject‒object issues framed within the topic of “tentative and essential return” through reinstatement of the animist conception of subjectivity, the subject on which Guattari worked passionately. Melitopoulos and Lazzarato argue that subjectivity is a superstition and advise that humanity move away from subject-centeredness; they further argue that the return of animism is not a return to irrationalism, that humanity should reinstate the subjectivity of animism as a natural state that is manifested multiple-simultaneously and unconsciously, through indeterminate forms of assemblages, such as individual entities and space, and architectural structures and affectless objects.

7. Examples include the following works shown as part of the Animism exhibition: the slide works of Marcel Broodthalers, the animal assembly painted by an unknown Ethiopian artist, and León Ferrari’s iconography of the dichotomy between animals and humans.

8. Works include, for example, animated productions by the Walt Disney Company to Isao Takahata’s Pom Poko (1994) and the neo-animist paradigm of Hayao Miyazaki, such as Princess Mononoke (1997). Thus, the animism discourse continued quite naturally through the symbolic discourses that are already very familiar to us.

9. Ontogenesis refers to a process of an embryo, or an egg fertilized by parthenogenesis—in other words an asexual embryo and spore—forming in an adult.

10. The Animism exhibit best matched to Simondon’s individuation theory is probably that by Daria Martin, titled Soft Materials (2004). In this work, she shows prosthetic body parts as machines that operate as metaphoric replacements for the human body. Martin thus explores the labor exchange-value between body and machine, and the mutually complementary articulation and pair-exchangeability between human and machine.

11. For example, The Love Life of the Octopus (1965), one in the series of twenty-three films entitled “Science is Fiction” by Jean Painlevé, or the “Nonhuman Rights” works by the Brazilian-born architect Paulo Tavares. These show intimate details of the intellectual capacities of the nonhumanity, or animality; the emotional expressions; cooperation among nonhuman life forms; and furthermore, the legal fights to secure equal legal and ethical rights based on the commonalities between the human and nonhuman. Works such as these are reflections of the pride and prejudice of the dichotomy between subject and object, and between nature and human, introduced by modernity.

12. On the cover of the first youth magazine in Korea, Red Chogori (붉은 저고리), there was the picture of a boy shaking hands with two tigers. The Youth, launched in 1914, also depicted a tiger whose head was being stroked by a young man.

13. “Chido ŭi kwannyŏm” [The concept of maps], Hwangsŏng Sinmun, December 11, 1908.

14. This translation and emphases in bold italics by the author. Atsushi Nakajima, Sikminchi chosŏnŭi p'ungkyŏng; trans. Kwan Choi and Jae Jin Yoo, Tiger Hunting. Seoul: Korea University Press, 2007, p. 47.

15. See pp. 66‒7 of Atsushi Nakajima, Sikminchi chosŏnŭi p'ungkyŏng; trans. Kwan Choi and Jae Jin Yoo, Tiger Hunting. Seoul: Korea University Press, 2007. This translation and emphases in bold italics by the author.

16. The term “ethnic abjection” was first used by Rey Chow in “The Secret of Ethnic Abjection.” Postcolonial theories have contributed to the global spread of the discourse of hybridity and cultural diversity as counter narratives to transnationalism and globalization. “Ethnic abjection” refers to the identity of heterogeneity that is being artfully concealed within this counterdiscursive frame and the emotional structure of the ambiguity, rage, pain, and melancholy brought about by the politics of recognition.

17. Lee Seung-bok was a nine-year-old South Korean boy brutally murdered by North Korean commandos in December 1968. The case of his murder was widely publicized throughout South Korea during the Park Chung-hee dictatorship. In the early 1990s, however, it was claimed by historians that his death was the creation of anti-communist propaganda since Lee had never existed.

18. Sakai’s critique (1999) on the myth of mono-ethnicity and the conceptualization of species within the domain of nation-states against Tanabe Hajime’s logic of species and the binary tropes of Nihonjinron challenged the particularism of postwar Japanese mono-ethnic nationalism while asserting ambivalent accountability of the particular and the universal. Sakai claims that the ambiguity of the logic of the Kyoto School scholars is entrapped within empirical terms such as race, ethnos, nation, folk, or the terms of Tanabe’s “species” (shu) and “genus” (ryu). This eventually exposes nationalism’s logical instability and its inability to conceptualize ethnicity/nationality of the particular/universal within the historically determined, therefore endlessly indeterminate categorization; and thus it is a dialectical process based upon individual negativity and facticity.

19. The wolves symbolize a metonym of the return of the primitive in the collective unconscious, as what Agamben (1998, p. 105) describes as “a monstrous hybrid of human and animal.”