I’d like to begin this talk with a Korean art movement.1 We frequently use the term “minjung (people’s) art”;2 however, in the 1980s, “minjok (national) art” was used more often to describe artistic practices based on anti-colonial, resistant nationalism. In the midst of the 1980s, I was still at university. And it is only thirty years before that the hot issues of Korean art had been traditional culture, minjok art, the form of minjok art, and so on. However, when we currently consider these terms, they sound like dead words, like the language favored in North Korea. Minjok art in the 1980s considered these terms, which represented the main, contentious issues among people in the period. These issues have certainly been dealt with in most of the so-called third world in which national liberation movements have occurred. At this time, the woodblock print was held up as a representative example of minjok art. People thought the woodblock print as a medium might constitute minjok art or entail forms of it. Nowadays, however, Koreans will come up with historical TV dramas when it comes to the minjok form of art, as the popularity of the word, minjok, has drastically declined over the period of the last ten to twenty years.

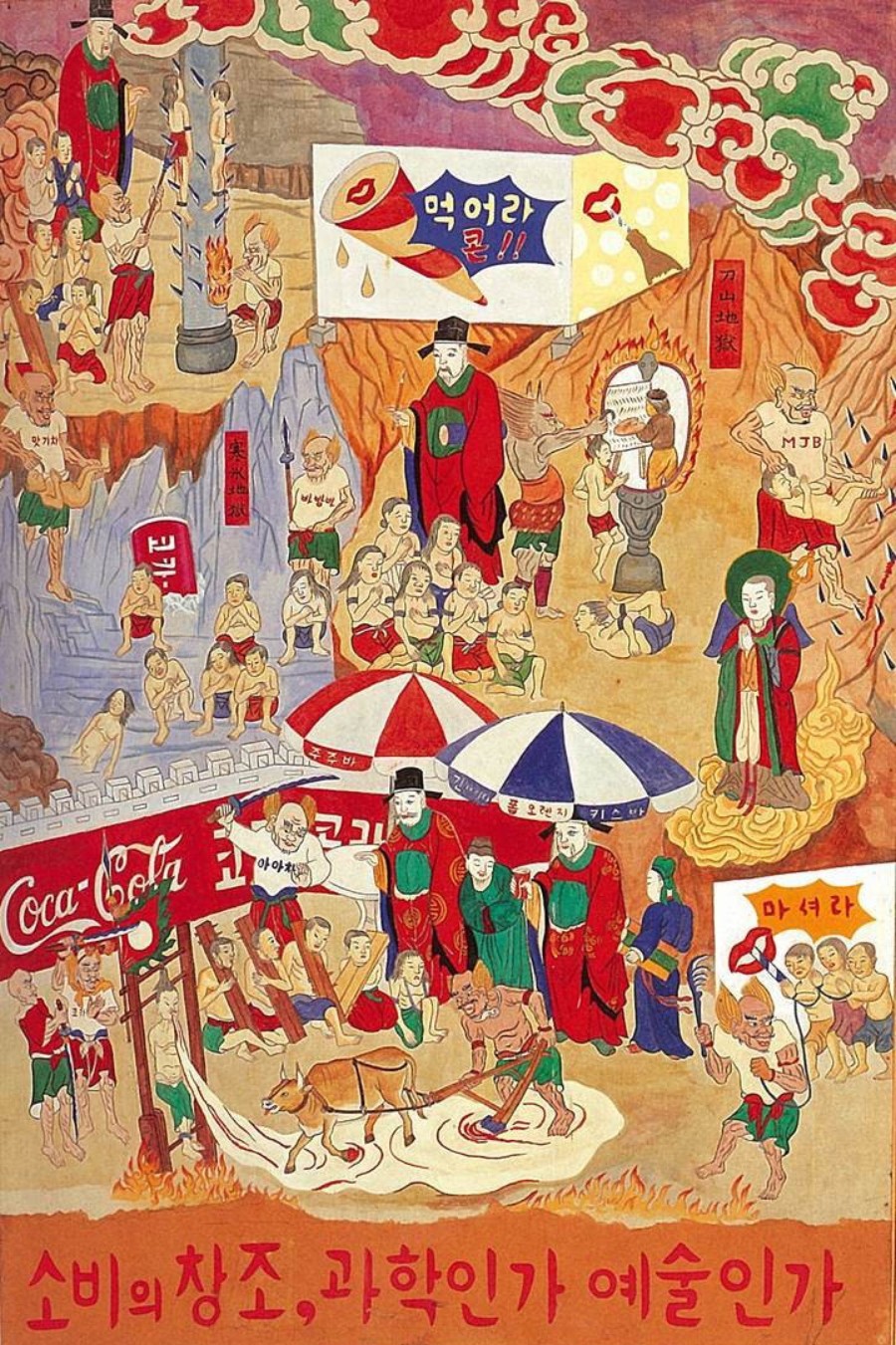

A couple of other, different examples include Oh Yun’s work in the form of traditional Buddhist paintings satirizing capitalism. However, it wasn’t just minjung art that highlighted minjok forms and traditions. Artists of dansaekhwa, or monochrome painting, an important part of Korean modern art, often suggested traditional porcelains or Eastern traditional landscape paintings as their core inspirations. For instance, art critic Won Dong Suk published a piece of critical text on artist Lee Ufan in the magazine Space, which I used to read when I was at high school. Won Dong Suk was one of the first-generation critics of minjung art. He stated in the text that Lee Ufan’s Eastern philosophy is pseudo- or false philosophy. This means, when minjung art was separated from modernism, traditional philosophy and culture served as key discursive platforms. In this respect, I would like to say that tradition as discourse once constituted a core podium and critical issue. And this was not accidental.

Oh Yun, Marketing 5: Hell, mixed media, 174 x 120 cm, 1981. © The family of Oh Yun

A few years ago, I visited an exhibition of Lee Ufan at a gallery in Berlin and checked out a pamphlet. It explained briefly about Ufan’s works in the introduction and talked about yeomhwamiso (拈華微笑), a well-known concept from Buddhism. Yeomhwamiso means that the Buddha and his disciple Kasyapa smiled together congenially. I could not understand in what context the Buddhist episode of yeomhwamiso would describe Lee Ufan’s works. I was familiar with art in general and read Buddhist scriptures from time to time, but could not clarify what this was supposed to mean. How would the majority of viewers in Berlin possibly understand this? Describing artworks using traditional Eastern anecdotes happens repeatedly everywhere, and those in the West may find this unfamiliar. This happens particularly often with Korean artists or Eastern artists based in Western countries. If ever any became successful, their works would be re-imported to Korea. This frequently prompts us, the Asians, to esteem Eastern artistic practice as the West does, even if we are not even fully aware of the works.

Before deciding whom to blame, whether the artists or the institutions of art, it still seems quite certain that the type of art mentioned above is a prime way to promote Asian artists within institutions and bet on their success. Among so-called international Korean artists, it is quite rare to find someone who has never dealt with the motif of being “Korean” or “Eastern.” Nam June Paik, with his own gat (a Korean traditional hat), often referred to East Asian ancient cultures or performed gut (traditional Korean rituals performed by shamans).

These issues, which are not as simple as various entanglings of the “symbolic institution” or the “politics of identity,” are more complicated and entrenched than they appear. In a state of cultural colonization—in other words, the state in which Western culture rules over the world—artists would think that they needed to make use of tradition, whether that tradition be called Korean culture or national culture. However, the question is which indications of Asian or Oriental tradition can be used to distinguish Korea from the West. I personally agree that it seems appropriate to see in general that no realistic criteria can create these divisions. Even if this is true, it does not mean that the qualities of tradition, nation, the East, or Asia are not significant or useful as pragmatic tools. It rather means that stressing tradition more than mere convention is more significant than it outwardly seems. It suggests more than relying on conventional binary divisions: Eastern wisdom as an alternative to Western civilization, the ethical comparisons between eating meat and vegetarianism, or of comparing saints, one of whom died standing up and was resurrected with one who died lying down and reached nirvana, and so on.

It can be discovered everywhere that these are not such simple questions. The majority of archives from seminars on Orientalism or tradition show attempts to discuss such complications. Lu Xun from China is a good example. In his texts the writer and thinker criticizes haughty Confucianists. However, he read the Confucian scriptures himself and very often quoted phrases from the books. He also sometimes represented himself as a Chinese nationalist. We can likewise observe confusing aspects from countless anecdotes regarding tradition or Western cultures. To put the issue to the fore, we can contemplate it in a more epistemologically dangerous way. It may be presumed that the Orientalism we criticize would play a crucial role in formulating decolonial turns or at least post-Western cultures within Western regions in the world, just as anthropology itself can become a tool for criticizing anthropology. On the other hand, white, male-dominated culture can use Asian Orientalist art as a mere means for masquerading its hypocrisy. But if so, is this always wrong? At the same time, this requires concrete analysis of artworks and well-articulated institutional critique. In addition, as we often see when Koreans study abroad in Europe and other places, they suddenly choose to practice “something Korean.” However, when they do something Korean, is it merely a cheap means to find a token of success in their identity game? Many of them would fall into the category, but some maybe not.

Western culture is superfluously dominant in both the West and the East, which I think is a significant loss to humanity. The poet and critic Kim Su-young3 once wrote that, “traditions, no matter how filthy, are good.” This can be a strategic lie or poetic exclamation. It may catch us red-handed like a ghost. The famous phrase above is excerpted from his poem, “Colossal Roots,” written in 1964. The poem is as follows:

I still do not know how to sit properly.

Three of us were having a drink. Two were sitting

with one foot resting on top of the knee, not cross-legged,

while I was sitting in southern style, simply cross-legged.

On such occasions, the other two being from the northern parts,

I adjust my sitting position. After Liberation in ’45, one poet,

Kim Pyong-wook, used to sit like a Japanese woman,

kneeling as he talked. He was tough; he spent four years

working in an iron company, attending university in Japan.

I am in love with Isabel Bird Bishop. She was the first head

of the Royal Geographical Society to visit Korea, in 1893.

She saw the dramatic scene as Seoul abruptly changed

into a world of women, men vanishing as a curfew gong rang.

A beautiful time: only bearers, eunuchs, foreigners’ servants,

and government officials were allowed to walk the streets.

Then she described how at midnight the women disappeared,

the men emerged, swaggering off to their debaucheries.

She had not seen any country with such a remarkable custom

anywhere else in the world, she said, while Queen Min,

who ruled the country, could never leave her palace [. . .]

Traditions, no matter how filthy, are good. I pass

Kwanghwamun, recall the mud there used to be by the wall,

remember how women heated cauldrons of lye

and did their washing by In-hwan’s hut in the stream bed,

filled in now, seeing those grim times as a kind of Paradise.

Since encountering Mrs. Bishop, it is not so hard for me

to put up with Korea, rotten country though it is.

Rather, I am awed by it. History, no matter how filthy, is good.

Mud, no matter how filthy, is good.

When I have memories ringing more resonant than a

brass rice-bowl, humanity grows eternal and love likewise.

I am in love with Mrs. Bishop, the progressives and socialists

are sons of bitches, unification and neutrality are all pure shit.

Secrecy, profundity, learning, dignity, conventions, should all

go to the security agency. Oriental colonization companies,

Japanese consulates, Korean civil servants, and ice cream, too,

should all go suck American cocks, but chamber-pots,

head-bands, long pipes, nursery stores, furniture shops,

drug stores, shoe shops, leather stores, pock-marked folk,

one-eyed people, barren women, ignorant folk: all reactions

are good, in order to set foot on this land. – Comparing

the underwater beams of the third Han River bridge

with the huge roots I am putting down in my land,

they are merely the fluff on a moth’s back, compared

with the huge roots I am putting down in my land.

Compared with those huge roots that even I cannot imagine,

suggestive of mammoths in horror movies,

with black boughs unable to entertain magpies or crows [. . .]

(February 3, 1964)4

In the beginning, he writes, “I still do not know how to sit properly.” In the second paragraph, reading a book about Korea written by Isabella Bird Bishop,5 who was a visitor to Korea, he repeats what she describes, that Korea is very odd with such a remarkable custom. There is plenty of inaccurate information in her book, however, here, it says Kim Su-young is in a relationship with Bird Bishop. Even if Bird Bishop had profound affection for Korea, she was a prominent Orientalist with an imperialist’s perspective. But looking at Korea through Bird Bishop’s eyes, Kim was able to fall in love with it. For example, “I pass / Kwanghwamun, recall the mud there used to be by the wall, / remember how women heated cauldrons of lye / and did their washing by In-hwan’s hut in the stream bed, / filled in now, seeing those grim times as a kind of Paradise. // Since encountering Mrs. Bishop, it is not so hard for me / to put up with Korea, rotten country though it is.” Here, he considers the gloomy period to be paradise and goes on to claim that all is filthy and rotten. Moreover, he exalts Bird Bishop by saying “When I have memories ringing more resonant than a / brass rice-bowl, humanity grows eternal and love likewise.”

The nonsense here is that Kim Su-young looks into himself with Bird Bishop’s eyes and falls in love with what he sees. His Orientalist reconsideration of his own memories, his poem’s foundation, and its structure, metaphorically imply a certain ambiguity, such as the definition of Orientalism, the difficulties of criticism, and so on.

Along with Korean monochrome painting, there were diverse discourses about modern hybrid culture, decolonialization, and postmodernism with regard to the debate about minjok art and modernism in the 1980s and 1990s. Briefly, to turn to another issue, there were times in the 1990s during which the politics of identity and code-subversion—subverting the West—were in prevalence and coincided with the retreat of nationalism in minjok art. Yiso Bahc, called Bahc Mo at the time this work was made, may be the pioneer of code subversion in Korea. Both Choi Jeong Hwa and Lee Bul’s works also suggest diverse forms of hybrid mimicry that doubt the purity of modernist culture or even destroy and ignore it. In this light, even if we ought to observe such things closely, I presume these artists thought to react to tradition in a certain way. It is plain, at least, that they considered tradition hugely significant. This is my personal view developed through my own way of reading artworks or my conversations with artists. I will move on to another subject.

Yiso Bahc, Weeds grow, too, 25 x 58 cm, ink on paper, 1988. © The family of Yiso Bahc

*

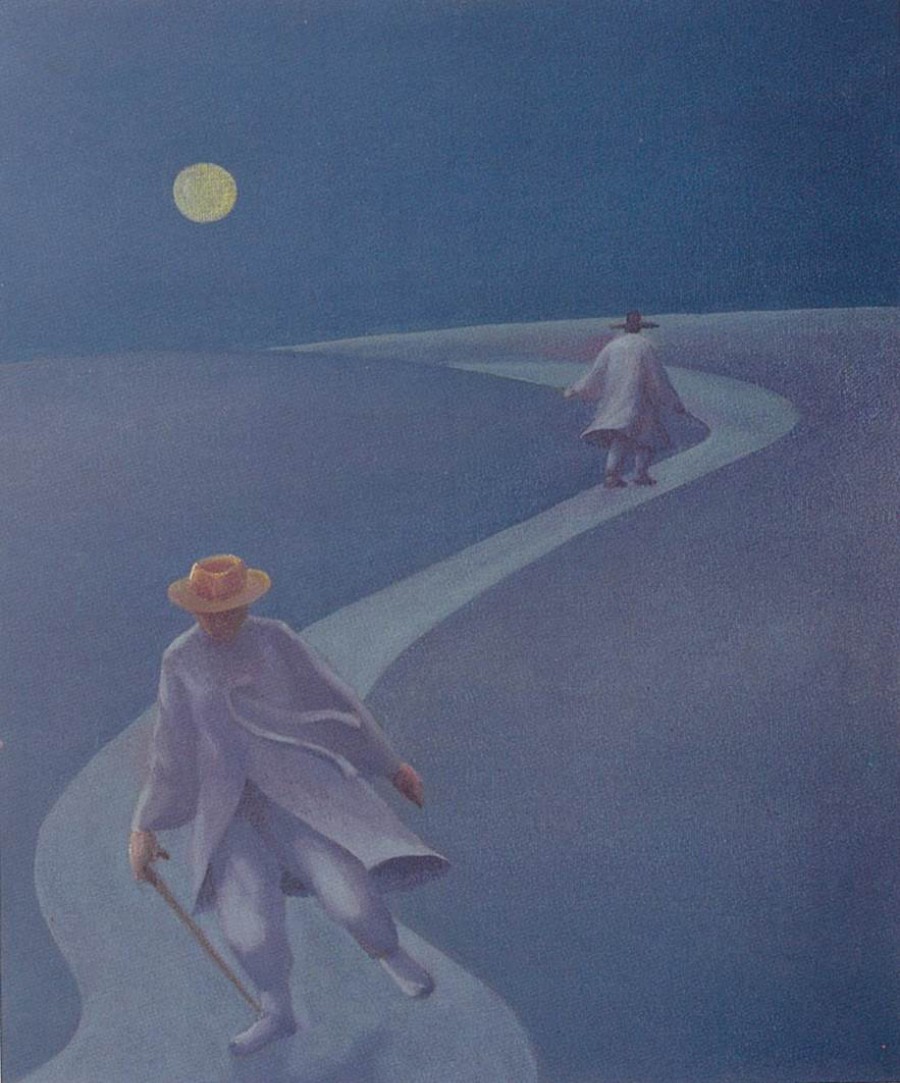

The point is that these artists take on tradition as a momentous issue. Even if it wasn’t often discussed among people, it is indispensable to pay more attention to the fact that minjung art was keen to express and elaborate the gaps between the traditional and the modern. The most representative minjung artists are Park Bul-ddong, Kim Jung-heon, Min Joung-ki, and Shin Hak Chul. When I first saw the exhibition Reality and Utterance,6 I was in my second or third year of high school. I was shocked. I thought through the cause of the shock and it turned out to be the compelling expression of different generations. I felt a discrepancy between older generations and mine. Since I moved to the Gangnam area in my early teens, the gaps between urban and rural areas and between the different eras represented in their works had an extreme affect on me. Thus, the core aesthetics of their works come from a kind of generational difference. This is a 1973 painting by Shin Hak Chul. An old man with a gat on his head walks limply on a hollow, empty road. The painful feelings of generational division may be caused by the contrived nature of contemporary society that results from the discontinuities between different eras or from the pain of having such an odd feeling. Following this, there is another issue about tradition. The works I have just mentioned are relatively renowned paintings.

Shin Hak-chul, Night Road 1, 38 × 45.5 cm, oil on canvas, 1973. © Shin Hak-chul

What I think about these paintings is that many critics of Orientalism and tradition, namely Eric Hobsbawm, see tradition as a subject or place for the fabrication of certain ideologies. Tradition, in any case, constitutes an entity of the continuity of time and demonstrates how its continuity can last for a very long time, for hundreds or thousands of years. Of course, a modern state could take advantage of the authority of tradition through inventing tradition. For example, mystifying Admiral Yi Sun-shin was a way the former president Park Chung-hee used and projected the history of the past for the sake of the current time.

If modernity stubbornly emphasizes the “here and now,” tradition, then, would highlight the “before, now, and after.” Whether or not modernity or the modern state use or do not use the authority of tradition through the “invention of tradition,” its continuity is a means of utilizing the past for the present. Conservatism (the untrustworthy link between the past and the present) is generated when the ideological usage of tradition and the fabrication of collective memory are integrated, with claims of the common truth of “the past, present, or future” and the causation of using the efficacy of the past to alienate the wrong elements of the present (keeping critical distance with the modern, relativization of modernity, etc.). This becomes even more complicated, as the two do need to be differentiated. Besides, when one attempts to use tradition to make sense of the present’s ruptures with the efficacy of the past or to make it a moment to look into the present in a bigger time-frame, we also become concerned with falling into the trap of the manipulation of ideology and the claim of truth. This could be another form of Orientalism. This is a concern as it may occur in reality.

I will elaborate more on this. We can ask if the “revival of tradition” employed for nation-state undertakings, which Western intellectuals criticize, can be applied to Asian countries with different histories as targets of criticism. If so, one can still question whether the methodologies of the West are valid. For instance, in Korea, institutions like national museums or state-designated cultural properties are constructed for the benefit of the nation-state. As institutions for the formulation of the nation-state they remain ideological. Despite this, some of those who have participated in such projects desperately say that, “tradition could have disappeared if we didn’t even have the apparatus. It might have all evaporated.”

I am questioning whether critiques of the nation-state or Orientalism can be solely justified in this context. To speak naively, we are often too afraid of Orientalism. Even if I, while living in the colonized cultural era, disapprove of Orientalism and choose the smoother and more intellectually persuasive sides, while hiding behind criticism of Orientalism, it still means a mere return to the myth called “modernity.” Don’t we have a tendency to regress toward what is evident and where there is no room for further criticism? Isn’t there any narrow-mindedness in the criticism of Orientalism? Is there even any colonial inclination to revere the West’s leftist views? Even the wild images of the rebels influenced by the Western leftists’ Orientalism may exist. In other words, we ought to look into questions of what theoretical and practical motivations are left after the criticism of Orientalism, or of what types of post-Orientalism can be encouraged and shaped.

*

To begin reaching a conclusion, Orientalism is an extremely complicated issue of overturning values in grasping each cultural object, whose solution is immensely demanding. We can detect countless examples of Orientalism and criticize them. This is the simplest level. We can also endlessly condemn the politics of envy toward the West. We can keep analyzing the cause of this inferiority and demythologize it with Roland Barthes’ idea of demystifying myth. However, is that enough?

The problematic reason why tradition is trapped within Orientalism is that tradition integrates with the fatigue of modernity and with the disappointment of Western culture as much as it relies on the myth of imperialism. Thus, the fact that the general frustration of Western modern civilization elevates the expectations of Zen Buddhism, meditation, and other practices cannot be solely identified as Orientalism. This, certainly, has generated typical Orientalist images. However, typical Orientalism also has its certain sincerities. For example, when the minjung movement or the student movement was fading out in the early 1990s, many of those who were frustrated sought isolated places such as training centers for gouksundo (Mountain Daoism). We consider linking such frustration to Daoist discipline as a retreat or an escape, but that may not be always true.

The success of dansaekhwa within institutions of art is not only attributed to the timely flow of diverse Orientalist markets (trends) or the modernist invasion of authorities in art departments in universities. It may be because the paintings look different from Western abstract paintings, as they are more peaceful, ornamental, and familiar to those who are exhausted by their complex urban lives. Wouldn’t such a painting go well with the pre-modern Joseon-era white porcelain at home? How innovative are Daoist concepts such as muwi (non-action) and jayeon (naturalness), even in this period during which one can hardly resist worldly desires? One commentator referred to Daoism as anarchism. Lee Ufan once claimed that dansaekhwa is resistance. I assume he might think so based on his background. (I am not declaring his claim is true.) Thus, Orientalism is hard to separate from demystification and ideological criticism; rather, what is required is a rupture, at aesthetic and even ontological levels involved in the reproduction of Orientalism.

In this light, it seems the essential issue still lies in “Korean paintings.” I think the Oriental painting departments at colleges in Korea, to speak generally, is a fruit of the Russo-Japanese wars. When Japan was victorious, it claimed the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, which resulted in Oriental painting departments in Japanese colleges, which in turn introduced the faculty into Korean colleges.

Take, for example, a work made in 2005 by Bomin Kim. The painting shows an Eastern painting-like view from the window of her studio. I’ve come to pay more attention to young artists like Bomin Kim, Jipyeong Kim (Jeehye Kim), Park Yoon Young, and Eunshil Lee. These artists majored in Oriental painting but diverged from the colleges’ official Eastern painting aesthetic. An intriguing aspect is that they share similar critiques such as the expression of the generation gap in minjung art, as mentioned earlier. They often represent the conflict between city and country, the unnatural speed of the condensed development of the city, or their doubts about Western cultures. The poet Jung Hyun-jong concisely summarizes this in his poem as “a strange land when eyes opened, home when eyes closed.” Min Joung-ki’s work, Embrace (1981), explains the phrase very well. Paintings that represent the generational gap or the friction between urban and rural areas have appeared from the so-called third world as well as from young Korean artists who rebelled against the Eastern art education in the 1990s. They also appear in Chinese art in the 1990s and 2000s.

Min Joung-ki, Embrace, oil on canvas, 112 x 145 cm, 1981. © Min Joung-ki

For example, similar issues are also found in literature, namely The Road to Sampo written by Hwang Sok-yong and short stories by Yun Heung-gil published in the 1970s. In the field of theater, there is an “overlapping effect” from Kang Baek Lee’s plays from the 1980s and 1990s. In this case, the past and the present occur at the same time on a stage. The past and the present are indicated at the same time so that a conflict can occur, which is also connected to the aesthetics of minjung art. The grouping of these Eastern paintings represents certain fresh ruptures from the Orientalism of Korean contemporary Oriental paintings (please bear with me if I cannot avoid using such absurd terms). Alternatively, in other words, they represent epistemological as well as chronological gaps.

I am interested in these practices and agree with their significance, but they have limitations. People often see that these works simply depict certain situations or make iconographic arrangements of symbols, such as works of the Reality and Utterance group. This is also true. As mentioned above, they stay at the level of ideological criticism as well as demystification. The entity of Orientalism cannot be shaken unless it goes through the full process of internalizing and incarnating Orientalism, overturning its values, and ceaseless competition between information and categories.

*

So far, we can think of certain diagrams and stages. First, there is an Orientalist level of Korean modernism. Second, is a post-Orientalist iconography that appeared recently in the artworks of Oriental painters and the early period of minjung art, including the Reality and Utterance group. Likewise, these can be seen as iconographic practices, “critical realism” without any particular realistic depiction. This is vital and very much shocking. However, to elaborate more, it has the same effect as decolonialist ways of deactivating Orientalist myths. It is similar to how literary critic Ko Mi Sook refers to Hong Myong-hui’s novel, Im Kkeokjeong,7 saying “the conceptions of sex during the Joseon period (1392‒1920) were not so conservative.” In other words, this seems to belong at the level of the linguistic operation of demystification. The problem is that this can constitute a valid partner to the existing or yet-to-flourish Orientalist market as well as the effeteness of the power of Orientalism. Minjung art can operate in the same way. Thus, we have to be able to come up with a third level. (Even if I am allocating different levels, it does not necessarily mean the levels are clearly defined.) We can consider another method using Western cultural terms, namely the grotesque, neo-Gothic, and the sublime. These words roughly match the Korean expressions I encountered in classical literature.

Epitomizing these features is a painting of Mt. Geumgang by Min Joung-ki. His animist landscape paintings are more important than they seem. The painting is not categorized as the typical landscape one sees from a distance, but rather one to be seen as a hallucination. It can be explained as animistic as well as an expansion of the animalistic senses interacting with nature. At this level, tradition is not semiotics or expression. Rather, it is a physical force, which can be felt by the body. Artist Kim Bongjun and critic Ra Wonshic, both of whom accentuated so-called conviviality, took into account these ideas. I think certain symptoms could be brought to the surface of Min Joung-ki’s paintings. Like the sublime aesthetic that delivers unknown subjects such as the grotesque or brings about unfamiliar experiences, we can imagine cosmological spaces or an odd cult-like pseudo-science philosophy. This can be linked to a form of cult, superstition, or post-Romanticist experience. This tendency leaves tradition beyond one’s perception. This can be seen also as an Asiatic repetition of the course of post-Romanticism or the neo-Gothic period, which would show that this sort of approach does not take into consideration its social roots.

Min Joung-ki, Manmulsang-Guemgang mountain, oil on canvas, 240 x 280 cm, 1999. © Min joung-ki

To return to the issue, people often claim to overcome the dualism of the East and the West or the conflicts between tradition and the modern. However, what are the main reasons for the constant failures of these attempts in reality, which leaves them to remain conceptual theories? It is because tradition is something that can be expressed in signs, language, or objects, but which does not exist in a tangible form. Conversely, we can also learn from the avant-garde turn of mind that, largely, was not restricted to objects.

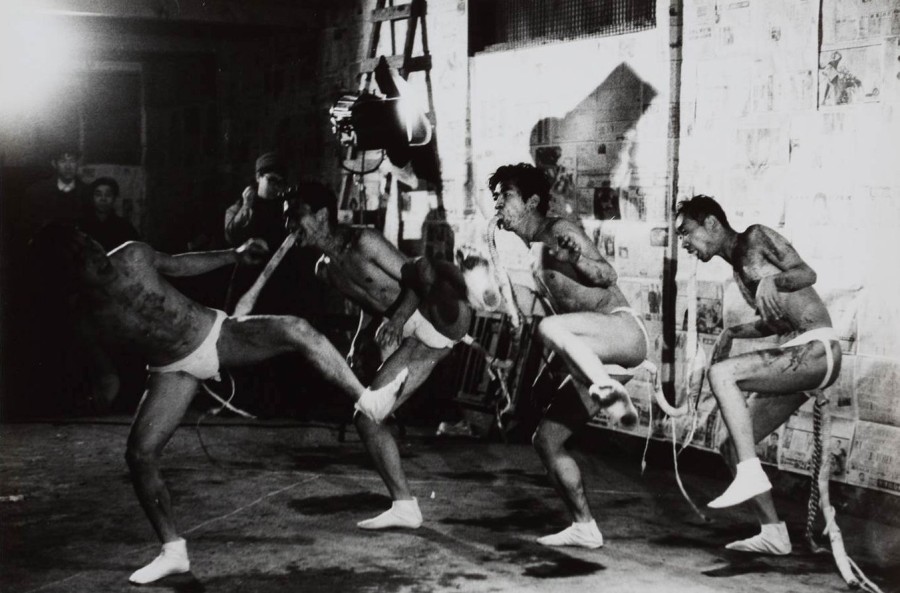

An artist group, Zero Dimension, which I introduced at the 2014 SeMa Biennale (Media City Seoul: Ghosts, Spies, and Grandmothers) attempts to integrate bodily intervention with the source of traditional cultures through avant-garde performance. Lygia Clark’s works, which dealt with Anthropophagy (Brazil’s cannibal tradition) and Lebanese writer and artist Jalal Toufic’s Ashura—This Blood Spilled in My Veins are valid examples that first come to my mind.

Zero Jigen in The Deserted Archipelago(無人列島), 1969, directed by Kanai Katsu. Photo by Kitade Yukio, © Kato Yoshihiro

Lastly, there is another stage at which tradition served as minjung (or subaltern) energy and the Liberation, a kind of “jumble,” which can be also be referred to as the “stage of gut.” Having minjung (or subaltern) interpellated by Kim Su-young’s poem “Colossal Roots” in artists Oh Yun, Park Saeng-kwang, and Lee Ungno’s depictions, is a success. However, the “colossal roots” in this context is the tradition that transcends simple depiction or iconography. In his phrase, “Traditions, no matter how filthy, are good,” the tradition is dirty and the poet still likes it, which indeed invokes physical memories beyond ideology. Thus, as the poet said, neither progressivism, socialism, unification, nor being neutral is significant. Therefore, this bears no relation to any lies such as the national archetype or the essence of Eastern cultures. Rather, tradition beyond iconography relates to ghosts, social sympathy, and solidarity.

What Kim Su-young claimed through the poem was tradition as a relationship that is linked to the presence of people, which transcends time. It is the tradition that resides beyond the imagery of minjung or the subaltern. Kim Su-young refers to the people who actively exist and transcend time, people who transgress time, and their presence, which is connected to tradition like small veins, which he depicts as huge roots. This is tradition to him. To return to the poem: while reading Bird Bishop, he comes to like “chamber-pots, / head-bands, long pipes, nursery stores, furniture shops, / drug stores, shoe shops, leather stores, pock-marked folk, / one-eyed people, barren women, ignorant folk [. . .].” These are his “huge roots,” greater than the underwater steel beams of the third Han River bridge.

Critiques of Orientalism tend to reject gut because much talk around Orientalism arose out of gut. However, if a critique of Orientalism avoids the object of its criticism it is also unsound. Criticizing Orientalism is fine, but a more flexible approach within the structure of Orientalism itself should be entailed in the criticism. Criticism of Orientalism should be better than Orientalism itself or contain certain surpassing elements within it. The criticism and the exceeder may conflict with each other. Even the critical reflection of “what is not Orientalism?” may be derived from outer, especially Western perspectives. This is imperative: what we can do in between escaping the Orientalist structure and demystifying it may even include intentional use of Orientalism. Kim Su-young, through much trial-and-error, finally used Bird Bishop’s perspective to see. He saw traditional Korean head-bands made of horsehair through Bird Bishop’s eyes.

My story reveals certain skepticism toward the “(international) universality of art.” The non-communicability and untranslatability between different local cultures are a mere superstition. However, even the universality that appeared in Matisse’s paintings can become more abundant through regional translations and versions. In this sense, skepticism of the universality of art, in this hectic period, and for everyone, is limited to the doubt about whether we are able to set aside such a long time to appreciate the universality. Such a long time, here, proposes the pitiful but valuable time to collect, attach, duplicate, and translate “little grass roots,” or so-called rhizomes, which constitute the huge roots; and most of all, it means the time to contemplate, imagine, and experience the longevity of minjung in the world.

This text is a transcript of a talk presented at the international symposium held on September 27, 2014, at Arko Art Center in Seoul. The symposium was held in tandem with the exhibition Tradition (Un)Realized curated by Hyunjin Kim, David Teh, and Jang Young Gyu.

In the Sino-Korean lexicon, the word “minjung,” combines “min” meaning “people” and “jung” meaning “masses.” Flourishing in the turbulent 1980s, minjung art was an artistic and social movement in which many individuals, groups, and collectives participated. Although most of the groups and collectives dispersed in the late 1980s, their members are still actively involved in artistic practice.

Kim Su-young (1921‒68), was a Korean poet and critic who advocated socially engaged poetry. A short introduction about the poet and his acclaimed poems are presented by the translator of many Korean poems, including “Colossal Roots” printed in this text. See Brother Anthony of Taizé’s website [online].

Excerpt from Kim Su-Young, Shin Kyong-Nim, and Lee Si-Young, Variations: Three Korean Poets, trans. Brother Anthony of Taizé and Kim Young-Moo. Ithaca, NY: East Asia Program, Cornell University, 2001 (bilingual edition), pp. 87‒89.

Isabella Bird Bishop (1831‒1904) was an English writer who traveled to many places in the world. Between 1894 and 1897, she visited Korea four times. Her travel notes and photographs were originally published in a volume Korea and her Neighbours […]. New York, et al.: Flemming H. Revell Company, 1897; this volume was translated into Korean and published by Charleston, South Carolina-based Nabou Press in 1994.

Reality and Utterance (Hyeonsilgwa bareon) is an artists’ group founded in 1979 in Seoul by artists and critics, including among others, Oh Yun, Sung Wan-kyung, Choi Min, Shin Hak Chul, Kim Jung-heon, Joo Jae-hwan, Min Joung-Ki, Kang Yobae, and Noh Wonhee. The Reality and Utterance group’s influential annual exhibition with the same name was held from 1980 through 1990 at which point they officially announced the group’s closure.

Im Kkeokjeong is an epic about the Joseon-era rebel by the same name. After Liberation in 1945, novelist Hong Myong-hui settled in North Korea and chose not to finish this novel, which he had begun to write in South Korea. The novel not only tells a story about the struggle of Im Kkeokjeong, but is rich in vernacular language as well.

1. This text is a transcript of a talk presented at the international symposium held on September 27, 2014, at Arko Art Center in Seoul. The symposium was held in tandem with the exhibition Tradition (Un)Realized curated by Hyunjin Kim, David Teh, and Jang Young Gyu.

2. In the Sino-Korean lexicon, the word “minjung,” combines “min” meaning “people” and “jung” meaning “masses.” Flourishing in the turbulent 1980s, minjung art was an artistic and social movement in which many individuals, groups, and collectives participated. Although most of the groups and collectives dispersed in the late 1980s, their members are still actively involved in artistic practice.

3. Kim Su-young (1921‒68), was a Korean poet and critic who advocated socially engaged poetry. A short introduction about the poet and his acclaimed poems are presented by the translator of many Korean poems, including “Colossal Roots” printed in this text. See Brother Anthony of Taizé’s website [online].

4. Excerpt from Kim Su-Young, Shin Kyong-Nim, and Lee Si-Young, Variations: Three Korean Poets, trans. Brother Anthony of Taizé and Kim Young-Moo. Ithaca, NY: East Asia Program, Cornell University, 2001 (bilingual edition), pp. 87‒89.

5. Isabella Bird Bishop (1831‒1904) was an English writer who traveled to many places in the world. Between 1894 and 1897, she visited Korea four times. Her travel notes and photographs were originally published in a volume Korea and her Neighbours […]. New York, et al.: Flemming H. Revell Company, 1897; this volume was translated into Korean and published by Charleston, South Carolina-based Nabou Press in 1994.

6. Reality and Utterance (Hyeonsilgwa bareon) is an artists’ group founded in 1979 in Seoul by artists and critics, including among others, Oh Yun, Sung Wan-kyung, Choi Min, Shin Hak Chul, Kim Jung-heon, Joo Jae-hwan, Min Joung-Ki, Kang Yobae, and Noh Wonhee. The Reality and Utterance group’s influential annual exhibition with the same name was held from 1980 through 1990 at which point they officially announced the group’s closure.

7. Im Kkeokjeong is an epic about the Joseon-era rebel by the same name. After Liberation in 1945, novelist Hong Myong-hui settled in North Korea and chose not to finish this novel, which he had begun to write in South Korea. The novel not only tells a story about the struggle of Im Kkeokjeong, but is rich in vernacular language as well.