Like a weakened body, the mind is prone to infection. It is perhaps even more vulnerable to infection than the body is. A 1967 CIA-funded documentary referred to the Chinese mood during the Chinese Civil War as a “gangrene of the spirit.”1 Heart disease is not merely material, but also psychic. Ideology affects both the material body and the immaterial mind. In Chinese, the word for heart (心) is also a word for the mind or for the soul. What one truly believes is what is in one’s heart.

If something can become infected, there must exist a state of non-infection—a state of purity (tabula rasa). Mental pathogens are certain ideas or lack thereof. Spiritual health implies a form of moral health, which can only be diagnosed when its symptoms are visible. No matter how dangerous some ideas might be, existing as physical brain states or immaterial thoughts, they can only help predict possible behavior, and all predictions are fallible. Ideas like diseases have a gestation period; they remain in the mind (or the heart) until such time that they become instantiated in the body—in action. Some people are carriers of conceptual pathogens and may never show the symptoms of an ideological illness. Some thoughts can lie dormant in the heart for decades. As the prophet Jeremiah put it, “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?”2

For the rationalists, it is only the soul that is truly free. The body remains mired in the cruel, deterministic laws of nature. The mind, as the Cartesian soul or the Kantian transcendental subject, can only be free by somehow inhabiting an incorporeal world exempt from the law of cause and effect. In this conception, the mind itself, like God to the theologians is a causa prima. “Free your mind…and your ass will follow.”3 A world without human free will would be a horrible existence of automatons following the dictates of heredity, circumscribed by the socioeconomic conditions of one’s birth, and victim to contingent natural events (not so different than the world of today). Without free will, we could not choose to do good or be moral. The idea of choice would make no sense. In fact, the entire American dream is based upon the confidence that we are metaphysically free. In Walt Disney’s misattributed words: “If you can dream it, you can do it.”4 Or as Barack Obama put it, “[American] values are rooted in a basic optimism about life and a faith in free will.”5

But our metaphysical agency is in doubt. Philosophical and scientific experiments have shown that free will might be an illusion, and that we sometimes merely imagine that we do certain things out of sheer volition. For example, electrical activity (Bereitschaftspotenzial) builds up in the physical brain before the conscious mind has any awareness of even making a decision. In other words, the conscious thought of our having chosen freely actually occurs after our brains have already prepared signals to be sent to the rest of the body. Once a bodily action is instantiated, it becomes a part of the objective world, and only then can it be given meaning, and only after a period of time, do we realize something has happened. According to the late neuroscientist Benjamin Libet:

Mental awareness can be delayed by up to ~0.5 s. Therefore, processes that are unconscious, that is without awareness, must precede it. If one extrapolates this situation for all mental events (admittedly without direct evidence), then all mental events are initiated and developed unconsciously. Indeed, most mental events are probably completely unconscious.6

MRI axial section of a subject.

© Dieter Meyrl, iStock

Only through repetition, can the mind make sense of things in the “buzzing, blooming confusion,” and only through reinforcement, is our view of the world created and sustained in the heart, for memory is repetition and reinforcement.

According to the BBC, “The Communist Party has complete control of the Chinese media. So the instructions go out and a way of thinking is simply poured into the community from above.”7 This overly simplistic description elides the existence of a rising Chinese civil society, which is increasingly influenced by various introspective interpretations of China’s past and its imagined future. Top-down impositions are not always accepted by the general populace, which is occasionally unsympathetic to and suspicious of the government’s media dictates.8 Moreover, Chinese historical consciousness is not merely spawned by the government, but also shaped by one’s own experiences and by repetitively told family stories of struggle and suffering that have been passed down from one generation to the next. The “Great Firewall of China” is an obvious example of ideological bias, but at least the Chinese government is openly unapologetic about its comprehensive censorship and surveillance program, unlike in some Western liberal democracies. Many, if not most, Chinese netizens are aware of media restrictions, and millions attempt to circumvent them every day. But this overt control over the media gives credence to the idea that the Chinese news is propaganda or “fake news.”

For there to exist fake news, there must exist a kind of “real news.” A lot of news, what counts as news in Taiwan, for instance, is a weak kind of fake news, because Taiwanese news stories are frequently too trivial even to be considered news (e.g. a new restaurant forgot to include free napkins). In these trivial cases, truth or falsity does not even matter. But the “fake” in fake news has a metaphysical component. What type of metaphysics is a criterion for distinguishing fake from real news? For most people, only another story or collection of stories can prove that some particular story is factually wrong (unless one actually witnessed the news-making event). There is no way for a regular reader to go above and beyond any particular news story to adjudicate its truth value from God’s point of view, so she can only arbitrate between competing stories filtered through her prejudices and biases. Furthermore, something is usually off about any news story—a detail, a nuance, the choice of words, implicit and explicit prejudices.

By definition, news is supposed to be a reporting of something noteworthy that has happened or is currently occurring. Here the presumed theory of truth is the correspondence theory: a news item is true because its referential content corresponds to a state of affairs that actually occurred in the recent past or obtains now. The news ostensibly reports facts. But the correspondence theory of truth, popular with philosophers for centuries, is not unproblematic. What exactly is the mysterious relationship between mental beliefs or news stories and physical objects in the real world? Can the news portray moral truth? (It probably aspires to.) Do moral facts exist? (Presumably no.) How are they represented and made true?

Consider this Guardian headline: “Trump anti-China tweet gives Rex Tillerson a fresh wall to climb.”9 How do we know or verify that it is true? Does the headline correspond to a fact which consists of some relationship between a Donald Trump tweet, Rex Tillerson, and some newly baked wall? Obviously, there is no literal wall that the U.S. Secretary of State needs to climb, and we accept that Trump wrote an “anti-China” tweet because of what we already read from the news about Trump’s hostile attitude toward China. And without a clear context, his tweet could be interpreted in different ways.10 The “reality” that makes Trump’s tweet and the Guardian’s headline true cannot be separated from the semantic and cultural rules that determine these very truth conditions. Following the late American pragmatist Richard Rorty, “nothing counts as justification unless by reference to what we already accept, and that there is no way to get outside our beliefs and our language so as to find some test other than coherence.”11

The coherence theory of truth replaces the isomorphism between language and the world with “coherence” among propositions or beliefs. So following this theory, the news is true when its referential content coheres with a view of the world, of the past, of language, and with that of other news. Taken to an extreme, following this theory of truth, a news item could be considered true, even if its propositional content referred to a state of affairs that does not actually obtain. A story could be false, but still be real news. (The New York Times’ stories about Saddam Hussein’s WMD come to mind.) A story is true because it is useful and it works—in society, for the pundits, and/or for the government. This sounds suspiciously like a pragmatic theory of truth, and it meshes nicely with a Nietzschean vision:

What, then, is truth? A mobile army of metaphors, metonymies, anthropomorphisms, in short a sum of human relations which have been subjected to poetic and rhetorical intensification, translation, and decoration, and which, after they have been in use for a long time, strike a people as firmly established, canonical, and binding […] the obligation to use the customary metaphors, or, to put it in moral terms, the obligation to lie in accordance with firmly established convention, to lie en masse and in a style that is binding for all.12

This is the principle of Chinese harmony—“和諧” (he xie), which means both harmony and, euphemistically, censorship. It is directly related to a Confucian (and pre-Confucian) tradition of prioritizing social order over individual expression and dissent. Critical discourse is allowed on the Chinese internet to some extent, but any calls for collective action are silenced. For many Chinese and especially for those who remember the turbulent and violent events of China’s recent past, harmony is preferable to chaos, as chaos breeds disease and leads to suffering and national humiliation.

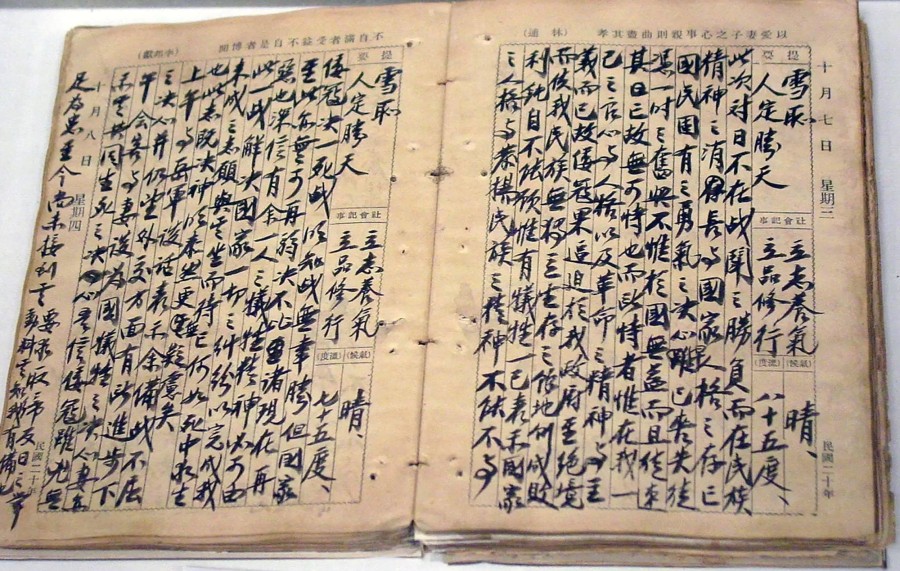

Nearly a hundred years ago, Chiang Kai-shek purportedly wrote “雪恥” (xue chi) into his diary every day for at least fifteen years.13 “雪恥” means “avenge humiliation” or “wipe clean shame,” as Chiang was referring to the malevolent actions of the Western and Japanese powers during China’s “century of national humiliation.” The second character in the traditional Chinese version of “雪恥” is built from the radicals for ear (耳) and heart (心). Humiliation or shame do not of themselves exist in the world like objects. They are the consequences of certain vibrations entering the ears and affecting the heart.

During the Second Sino‒Japanese War, Chiang famously claimed that the Japanese were merely a disease of the skin, whereas the communists were a disease of the heart.14 He knew that the Japanese would eventually be defeated by the Allies, but he was still to face the communists, who were spreading their ideational contagions throughout the rural Chinese heartland. If the communists were victorious, not only would the peasants get the land, they would also have their revenge against the landowners. Merely convincing the mind was doomed to failure; one also had to pacify the heart (贏得民心). The English expression includes both “hearts and minds.”15 In other words, a purely cognitive approach is insufficient to explain or motivate the emotional and moral aspects of belief. Faith, as an infection, is too deep.

In 2006, the Hoover Institution exhibited the hand-written diary of Chiang Kai-shek from the years 1917 to 1931.

© Central News Agency

Chiang was perhaps also alluding to one of China’s celebrated ancient physicians and to the possibility of losing to the communists. Regarded as the founder of Chinese traditional medicine, Bian Que (扁鵲), reportedly, lived during the Zhou Dynasty, between 500 and 600 BCE. According to legend, the doctor encountered a nobleman and diagnosed a disease of the skin. Without obvious, visible symptoms, the nobleman ignored the doctor’s repeated admonitions, even as the disease began to attack the nobleman’s organs. Later, the infection traveled to the nobleman’s bone marrow and killed him. Chiang’s relentless operations against the communists were his unheeded warnings. It took his kidnapping by a warlord during the 1936 “Xi’An Incident” to finally convince him to collaborate with the communists against the invading Japanese. Additionally, in another fable from a chapter of the Daoist text, the Liezi (列子), called “Exchanging hearts and minds,” Bian Que apparently performed a successful heart transplantation—something Chiang never had the chance to complete.16

For some, the epoch of national humiliation did not end with the communist revolution. China and the Chinese are still sick. According to a well-known American sinologist, the “moral crisis that has plagued China for well over a century continues today.”17 Confucian culture, even though in resurgence, has been under attack ever since the fall of the Qing Dynasty in the early twentieth century. Communism, the titular aim of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has given way to capitalism, materialism, and corruption. Middle-class Chinese save money to send their children to overpriced Western schools, and Chinese families jump at the chance of leaving the Mainland for an unpolluted and boring suburb in some developed Western country, preferably the United States. Chinese affluence does not necessarily translate into patriotism, and moneyed, prospective immigrants seem to lack any faith in the future of their motherland. Millions of people around the world and in the U.S. aspire to become Americans. How many desire to become Chinese?

American nationalism was essential to the Allied victory in the Second World War and is still indispensable for American dominance today. The Pacific War was fueled by racist nationalist sentiment, which was easily recast during the Korean and Vietnam wars, and which is being further adapted to the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East. Inside the East Asian security umbrella, American domination and wealth creation transformed American nationalism into a generally tolerated and sometimes welcomed “enlightened” or “liberal” nationalism.

This species of “benign” American nationalism is contrasted with the nationalism of developing or non-Western nations. Western pundits use the word “virulent” to describe anti-Western nationalistic ideologies. Non-American or un-American nationalist positions are seen as dangerous and threatening, and developing nations risk being accused of engaging in “assertive” or “reactive nationalism,” whenever their actions don’t jibe with the celebrated American status quo.

But now the Americans are the sick ones, and populist virulence has, by the Western media’s own measure, exploded in Europe and the U.S. Protests and racist or politically motivated violence are commonplace in American media and have become the norm—even boring. Benign nationalism has become malignant.

Western tribulations have turned the world upside down. China is now a beacon of globalist capitalist stability, and America the unstable power, torn asunder by internal political strife. Perhaps this is the real face of China, as it is the real face of America. Despite massive rebellions, natural disasters, and an ancient history of dynastic warfare, China might actually be and have been the stable civilization, and America the capricious flash in the pan: fit to bursts of anger, murderous invasions, political confusion, and childish whims. In pathogenic terms, the pustules of democracy (and theocracy) have erupted, spewing malodorous ideologies that cannot be killed by sunlight, Platonist or otherwise. It was once claimed that if you scratch the skin of any person in the world, you would eventually reach an American; perhaps now, you will get a Chinese. America (and the West) can simply no longer be trusted.

The “gangrene of the spirit” can be described as a moral, spiritual vacuum—a nihilism. What Christians might call a “God-shaped hole” is now a way of life. Liberal democracy, neoliberal capitalism, and unfettered technological progress can be summed up in John Lennon’s words: “Nothing to kill or die for / And no religion too.” Contemporary social indicators are symptoms of modern nihilism: unemployment, heart disease, obesity, laziness, depression, anxiety, and homelessness. Following the logic of retired statesman Bill Clinton, the globalist, neoliberal economic system as nihilism has led to a search for value, exceptionality, and character: “It’s like we’re all having an identity crisis at once—and it is the inevitable consequence of the economic and social changes which have occurred at increasingly rapid pace.”18

If we focus on the economic giants of East Asia, we see that China and Japan both maintain flourishing nationalistic enterprises, the strongest being their very own governments. Japan’s government was only able to promote its imperial nostalgia under a less and less watchful American eye, which is prone to turning away whenever Japanese nationalistic fervor tolerates or encourages American interests. After the international failures of actually existing socialism, the CCP untethered itself from the increasingly anachronistic notions of Marxism-Leninism and Maoist thought, and instead put its energies into promoting a shared sense of Chinese national identity. This modern Chinese nationalism feeds on its Japanese variant in a sort of feedback loop, fueled by their respective nationalistic media.

If current events are any indicator, China and Japan are still competing for East Asian regional dominance. China as a civilization was once the undisputed leader of East Asia, with the rest of East Asia and most of Southeast Asia regulated to the status of tributary or subservient territories. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Japan displaced China as regional hegemon by modernizing and industrializing rapidly during the Meiji Restoration and then by killing millions. China’s staggering postwar death toll followed from disastrous and sometimes murderous, domestic social policies, rather than from expansionist, aggressive war.

Japan attempts to keep track of the majority of its own Japanese war victims. As an ultranationalistic entity, Yasukuni Shrine serves this archival function, and the Yushukan Museum on the grounds of Yasukuni features the pictures of thousands of Japanese (and non-Japanese) soldiers who fought and died for the emperor.

In contrast, millions of Chinese victims remain nameless and faceless. Here, one problem is numbers. Describing China, postwar American propaganda frequently referred to the “masses”—the great, almost inconceivable, number of Chinese who were indistinguishable as individuals to Westerners and to various Chinese administrations. Some sinologists, those who are supposed to know and care about China, like to refer to the collective “Chinese mind” or the “Chinese mentality,” which is necessarily inferior politically, culturally, and rationally to the West’s. By the same token, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek referred to modern China as a series of anonymous cities of millions.

A slow day at Shanghai Hongqiao Railway Station.

© James T. Hong

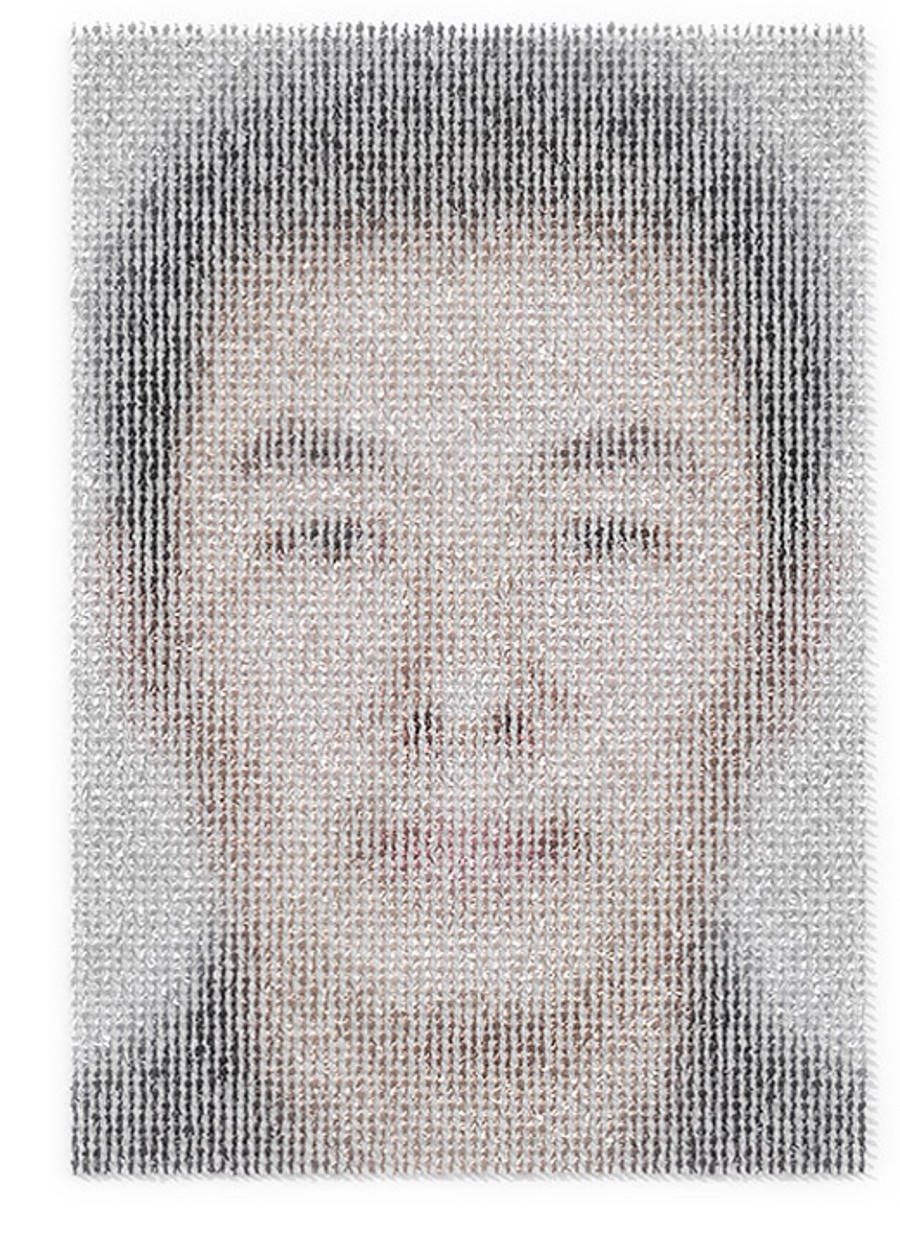

To the thousands of evangelical Christian missionaries who have tried and are still trying to convert China’s masses, every Chinese person is the same, because every Chinese soul is identical to any other Chinese soul. This civilizing attitude of metaphysical egalitarianism now also applies to the material Chinese body. According to a 2011 report by National Geographic, the most typical person in the world is a twenty-eight-year-old Han Chinese male. The “experts” who compiled this report created a picture of the world’s most common face by compositing nearly 200,000 Chinese faces together (I am curious if the compilers remembered just how important the concept of face is). Undifferentiated and interchangeable, the Chinese is cursed with the burden of being generic and thus, of being disposable.19

The most typical person in the world. Illustration by Bryan Christie Design for National Geographic Magazine

Like his soul, the Chinaman’s heart is also indistinguishable from any other. Walt Disney was completely wrong when he apocryphally claimed, “The more you are like yourself, the less you are like anyone else, which makes you unique.”20The sickness is numerical anonymity, for no matter what the most typical person achieves, his individual efforts, if acknowledged at all, will not be recognized as anything but ordinary. Western racial theorists already claimed over one hundred years ago that the Chinaman “tends to mediocrity in everything […] he does not dream or theorize; he invents little […] no civilized society could be created by them; they could not supply its nerve force, or set in motion the springs of beauty and action […] the Chinese are glad to vegetate.”21

Furthermore, no matter what the Chinaman does, he will always be subject to Western statisticians, psychologists, and prejudices; his destiny is that of an analytical sample, a probability distribution, or a trend. He is cursed with being the mean. As fallible, unfree, and ubiquitous, he will always be denigrated, humiliated, and made smaller—he will never be allowed to finally stand up. In 2008, this attitude was expressed in a viral, anonymous poem:

When we were the Sick Man of Asia,

We were called the Yellow Peril.

When we are billed as the next Superpower, we are called The Threat.

When we closed our doors, you launched the Opium War to open our markets.

When we embraced free trade, you blamed us for stealing your jobs.

When we were falling apart, you marched in your troops and demanded your fair share.

When we tried to put the broken pieces back together again, Free Tibet, you screamed. It was an Invasion!

When we tried communism, you hated us for being communist.

When we embraced capitalism, you hated us for being capitalist.

When we had a billion people, you said we were destroying the planet.

When we tried limiting our numbers, you said we abused human rights.

When we were poor, you thought we were dogs.

When we lend you cash, you blame us for your national debts.

When we build our industries, you call us polluters.

When we sell you goods, you blame us for global warming.

When we buy oil, you call it exploitation and genocide.

When you go to war for oil, you call it liberation.

When we were lost in chaos, you demanded the rule of law.

When we uphold law and order against violence, you call it a violation of human rights.

When we were silent, you said you wanted us to have free speech.

When we are silent no more, you say we are brainwashed xenophobes.

Why do you hate us so much? we asked.

No, you answered, we don’t hate you.

We don’t hate you either,

But do you understand us?

Of course we do, you said,

We have AFP, CNN and BBC… [. . .]22

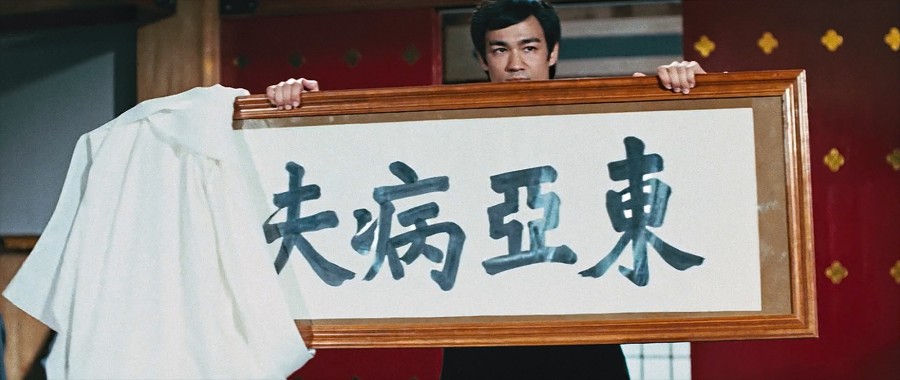

Bruce Lee holding a "sick man of East Asia" sign. Film still from The Fist of Fury (1972), directed by Lo Wei.

© 2010 Fortune Star Media Limited All Rights Reserved

So the most typical person in the world might think to himself: If I am not unique, memorable, or special in any way, perhaps my family is or can be. But here the numbers are against him as well. The most common person in the world is probably named Li, Wang, Zhang, or Chen, and those surnames, like countless others, are shared by millions of other anonymous, unexceptional people just like himself. Not only is the Chinese generic, so by extension is his family.

This reasoning eventually leads the most typical person in the world to the nation, or more precisely, to the idea of the nation. According to Anthony Smith, “The nation was always there, indeed it is part of the natural order, even when it was submerged in the hearts of its members.”23 Individual narcissism is pointless, as the Chinaman cannot stand out from the crowd—he is the crowd.

If the most typical of people cannot by himself rise to greatness, then perhaps his country can, and history might finally achieve a happy Hegelian ending. In other words, history (as progress) could end in China. Even if this state of affairs seems improbable now, it is not impossible. The political scientist Yan Xuetong says very clearly:

If China wants to become a state of humane authority, this would be different from the contemporary United States. The goal of our strategy must be not only to reduce the power gap with the United States but also to provide a better model for society than that given by the United States.24

Unlike the Russian separatist or the ISIS fighter, the Chinese ultranationalist doesn’t need to hide his face—it is already anonymous. If his country rises to national greatness, if it becomes the regional hegemon, if it becomes a true superpower, then the associated national uniqueness, international prestige, and begrudging respect will trickle down to all of its citizens, and the most typical person in the world will now no longer be so typical.

This is the Chinaman’s chance.

“In fifty years of barbarism, a gangrene of the spirit has set in.” China: Roots of Madness, dir. Mel Stuart. U.S. Made for TV documentary, David L. Wolper Productions, 1967.

Jeremiah 17:9, English Standard Version Bible.

The next line is “The kingdom of heaven is within.” Funkadelic, “Free your mind…and your ass will follow,” on the album Free Your Mind…and Your Ass Will Follow. Detroit: Westbound Records, 1970.

See Walt Disney quote at Wikiquote [online].

Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream. New York: Crown Publishers, 2006, p. 54.

Benjamin Libet, “Reflections on the interaction of the mind and brain,” in Progress of Neurobiology, vol. 78, nos 3‒5 (2006), pp. 135‒326, here p. 324.

Stephen McDonell, “China fuels anger over Seoul’s missile move,” BBC News online China Blog, March 13, 2017 [online].

“Domestic media institutions that cannot adapt to the new situation continue reporting the world as they used to, which is different from the daily experiences of ordinary people. This has resulted in people’s lack of trust in State-run media outlets.” See “State media should play due role in properly guiding public opinion,” China Daily, February 22, 2016 [online].

Tom Phillips, “Trump anti-China tweet gives Rex Tillerson a fresh wall to climb,” the Guardian, March 18, 2017 [online].

Donald J. Trump, Twitter, 9:07pm ‒ Mar 17, 2017: “North Korea is behaving very badly. They have been ‘playing’ the United States for years. China has done little to help!” Perhaps he means that China has done little to help North Korea “play” the U.S.

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 178.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense,” in The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings, trans. Ronald Speirs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 146.

Timothy Cheek, The Intellectual in Modern Chinese History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 77.

Chiang’s diaries are housed at the Hoover Institution in California, where access is restricted and copying forbidden. Given the historical importance of Chiang Kai-shek to the modern history of China and Taiwan, doesn’t it make more sense for his diaries (or at least a copy of them) to be housed in an archive in Taiwan or perhaps China? The fact that they’re in the U.S., under lock and key, demonstrates the U.S.’ political relationship to Taiwan and China.

China: Roots of Madness, dir. Mel Stuart. U.S. Made for TV documentary, David L. Wolper Productions, 1967.

According to The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2007, p. 294: “This is the true meaning of the phrase ‘hearts and minds,’ which comprises two separate components. ‘Hearts’ means persuading people that their best interests are served by COIN [counterinsurgency] success. ‘Minds’ means convincing them that the force can protect them and that resisting it is pointless.”

In English, see Lieh-Tzu: A Taoist Guide to Practical Living, trans. Eva Wong. Boston, MA: Shambhala, 2001, p. 54.

Anne Thurston, “Community and Isolation; Memory and Forgetting: China in Search of Itself,” in Gerrit W. Gong (ed.), Memories and History in East and Southeast Asia: Issues of Identity and International Relations. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2001, p. 168.

Bill Clinton, remarks at the Brookings Institution at the launch of a biography of Yitzhak Rabin, March 9, 2017, video [online].

U.S. General William Westmoreland had the same attitude when he claimed that “Life is plentiful; life is cheap in the Orient.” From Hearts and Minds, dir. Peter Davis. USA: BBS Productions and Rainbow Releasing, 1974.

See Matt Novak, “8 Disney Quotes That Are Actually Fake,” Gizmodo, March 19, 2015 [online].

Arthur de Gobineau, The Inequality of the Human Races, trans. Adrian Collins. New York: Howard Fertig, 1999, pp. 206‒7.

Anthony D. Smith, Myths and Memories of the Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 180.

Yan Xuetong, Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power, trans. Edmund Ryden. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011, p. 99.

1. “In fifty years of barbarism, a gangrene of the spirit has set in.” China: Roots of Madness, dir. Mel Stuart. U.S. Made for TV documentary, David L. Wolper Productions, 1967.

2. Jeremiah 17:9, English Standard Version Bible.

3. The next line is “The kingdom of heaven is within.” Funkadelic, “Free your mind…and your ass will follow,” on the album Free Your Mind…and Your Ass Will Follow. Detroit: Westbound Records, 1970.

4. See Walt Disney quote at Wikiquote [online].

5. Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream. New York: Crown Publishers, 2006, p. 54.

6. Benjamin Libet, “Reflections on the interaction of the mind and brain,” in Progress of Neurobiology, vol. 78, nos 3‒5 (2006), pp. 135‒326, here p. 324.

7. Stephen McDonell, “China fuels anger over Seoul’s missile move,” BBC News online China Blog, March 13, 2017 [online].

8. “Domestic media institutions that cannot adapt to the new situation continue reporting the world as they used to, which is different from the daily experiences of ordinary people. This has resulted in people’s lack of trust in State-run media outlets.” See “State media should play due role in properly guiding public opinion,” China Daily, February 22, 2016 [online].

9. Tom Phillips, “Trump anti-China tweet gives Rex Tillerson a fresh wall to climb,” the Guardian, March 18, 2017 [online].

10. Donald J. Trump, Twitter, 9:07pm ‒ Mar 17, 2017: “North Korea is behaving very badly. They have been ‘playing’ the United States for years. China has done little to help!” Perhaps he means that China has done little to help North Korea “play” the U.S.

11. Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979, p. 178.

12. Friedrich Nietzsche, “On Truth and Lying in a Non-Moral Sense,” in The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings, trans. Ronald Speirs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 146.

13. Timothy Cheek, The Intellectual in Modern Chinese History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 77.

Chiang’s diaries are housed at the Hoover Institution in California, where access is restricted and copying forbidden. Given the historical importance of Chiang Kai-shek to the modern history of China and Taiwan, doesn’t it make more sense for his diaries (or at least a copy of them) to be housed in an archive in Taiwan or perhaps China? The fact that they’re in the U.S., under lock and key, demonstrates the U.S.’ political relationship to Taiwan and China.

14. China: Roots of Madness, dir. Mel Stuart. U.S. Made for TV documentary, David L. Wolper Productions, 1967.

15. According to The U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2007, p. 294: “This is the true meaning of the phrase ‘hearts and minds,’ which comprises two separate components. ‘Hearts’ means persuading people that their best interests are served by COIN [counterinsurgency] success. ‘Minds’ means convincing them that the force can protect them and that resisting it is pointless.”

16. In English, see Lieh-Tzu: A Taoist Guide to Practical Living, trans. Eva Wong. Boston, MA: Shambhala, 2001, p. 54.

17. Anne Thurston, “Community and Isolation; Memory and Forgetting: China in Search of Itself,” in Gerrit W. Gong (ed.), Memories and History in East and Southeast Asia: Issues of Identity and International Relations. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2001, p. 168.

18. Bill Clinton, remarks at the Brookings Institution at the launch of a biography of Yitzhak Rabin, March 9, 2017, video [online].

19. U.S. General William Westmoreland had the same attitude when he claimed that “Life is plentiful; life is cheap in the Orient.” From Hearts and Minds, dir. Peter Davis. USA: BBS Productions and Rainbow Releasing, 1974.

20. See Matt Novak, “8 Disney Quotes That Are Actually Fake,” Gizmodo, March 19, 2015 [online].

21. Arthur de Gobineau, The Inequality of the Human Races, trans. Adrian Collins. New York: Howard Fertig, 1999, pp. 206‒7.

22. Purportedly written by Chinese American physicist Duo-liang Lin, but provenance unverified. Retrieved from the Washington Post, May 18, 2008 [online]; also [online].

23. Anthony D. Smith, Myths and Memories of the Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 180.

24. Yan Xuetong, Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power, trans. Edmund Ryden. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011, p. 99.