Today, our use of the term “media” is dominated by communication technologies. But etymologically there is considerable multivalence in the concept of media. Art history and media theory, for example, do not operate with the same understanding: in art history, “medium” might refer to a genre of art and to the materials in which it is executed; in media theory, the concept extends variously to technological, cultural, social, and even psychological phenomena. In European thought, the term “medium” was historically tied to “milieu” and “environment.” It originally applied to all of nature, seen as a mediation between the divine and the human, and as the medium in which natural phenomena—such as the refraction of light in water—occur. Later it referred to unseen forces including electricity and intangible transmissions as in hypnosis, spiritism, and trance rituals.1 Hence, “medium” refers on the one hand to the invisible transmissions and the relation between organisms and their environments, and on the other, to the insurmountable condition of being-in-a-medium—such as a community bound by language.

Lieko Shiga, A Portrait of Cultivation from the “Rasen Kaigan” series, 2009.

© Lieko Shiga

The anarchism of possible meanings that preceded the identification of the term “medium” with technological media reflected, in a symptomatic and phantasmatic way, the ontological upheaval of nineteenth-century modernity, both in its industrial and colonial dimensions. Greater technical mediation implies more uncertainty over the constitution of sense and the mediatedness of human subjects. The notion of mediation opened up over this modern abyss, as the result of an ontological drift and the radical uncertainty cast over previous templates of collectivity.

That ontological opening resulted in a colonization of just what we are able to accept and understand as “medium.” To the (male, white) rational autonomous subject, human mediumship—in all its dimensions, including that of emergent mass psychology—became a growing source of anxiety, emblematic of everything deemed irrational since the dawn of colonial modernity. But the battle against ritual possession, spirit media, and shamanism, as well as the real exclusions of typically gendered forms of affective mimetic behavior was simultaneously accompanied by an imaginary appropriation of those very practices by the culture of the colonial metropolis—in the form of abounding fantasies of primordial channels and mighty transmissions. The eminent theoretician of media at the dawn of the “dematerialized” Information Age, Marshal McLuhan, saw in all Western culture a “crescendo of primitivisms.”

Already the Enlightenment sought carefully to distinguish figments of the imagination from systematic and rational accounts of reality: but in so doing, it created a language of rationality only capable of accounting for human agency and its effects. The Age of Reason could not grapple with the inverse; namely, how we are not only acting, but also acted upon; how not only do we produce symbolic systems, but are equally produced by them. In the twentieth century, the phenomena of mediumism were partitioned along the lines of the different disciplines of knowledge and ultimately relegated to psychology, religion, and art on the one hand, and to computation on the other. This, in turn, left a large void in our accounts of culture, produced in particular by the absence of a critical language for the mediated nature of sociality and subjectivity in relation to history, technology, and ideology. The degree to which modern technological media exist in continuum with the phenomena of mediumism has hence been obscured. But the term “media” carries its colonial and spiritual histories in its unconscious, and that unconscious, in turn, can only be thought of as a realm of mediality where those very divisions are destabilized—or even categorically undone—in the moment of their rearrangement.

The recent works of artists Ho Tzu Nyen and Chia-Wei Hsu put forward an expanded notion of media and mediality against the backdrop of colonial modernity, in which “old” and “new” media are juxtaposed to effect such a destabilization and rearrangement. This demands that art history engage with both the colonial foundations of modernity as well as the transhistorical temporalities of the psyche, and equally challenges media theory with its focus on technology.

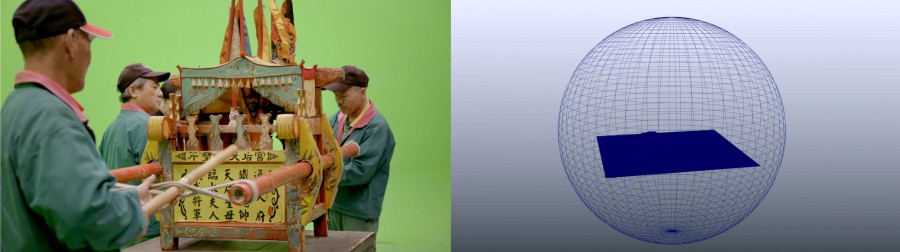

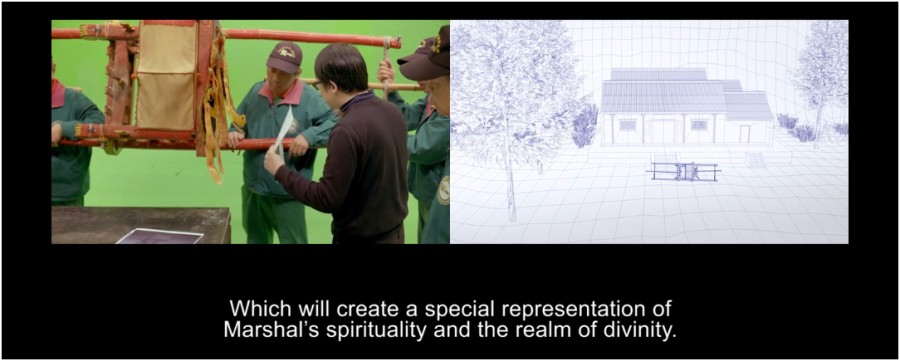

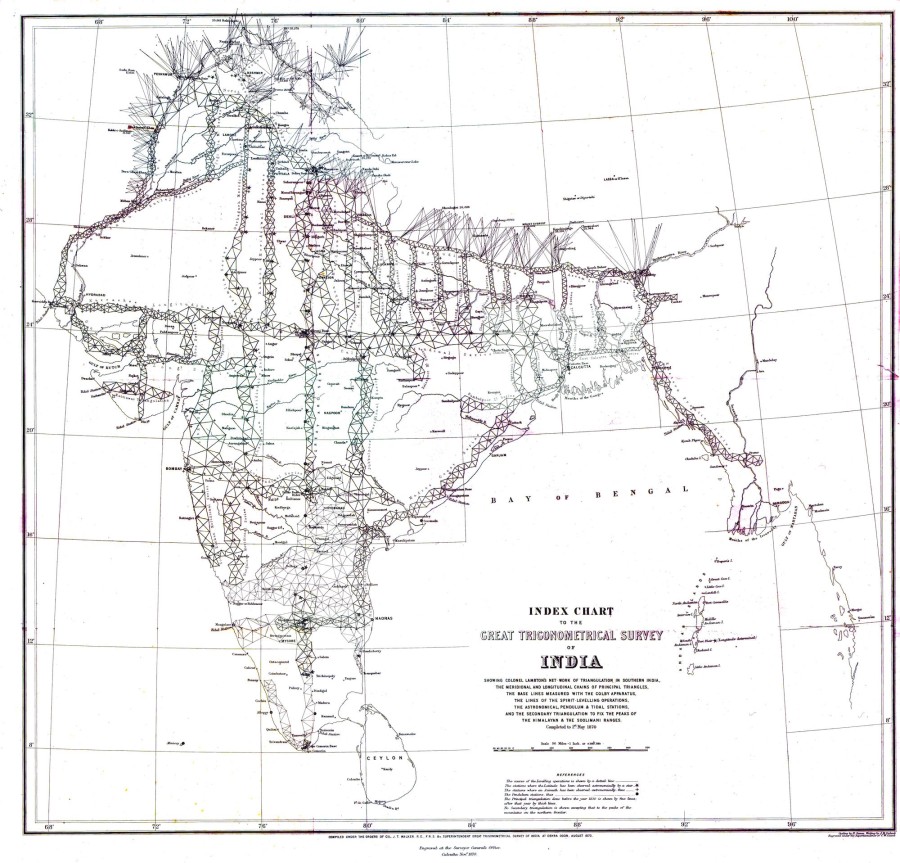

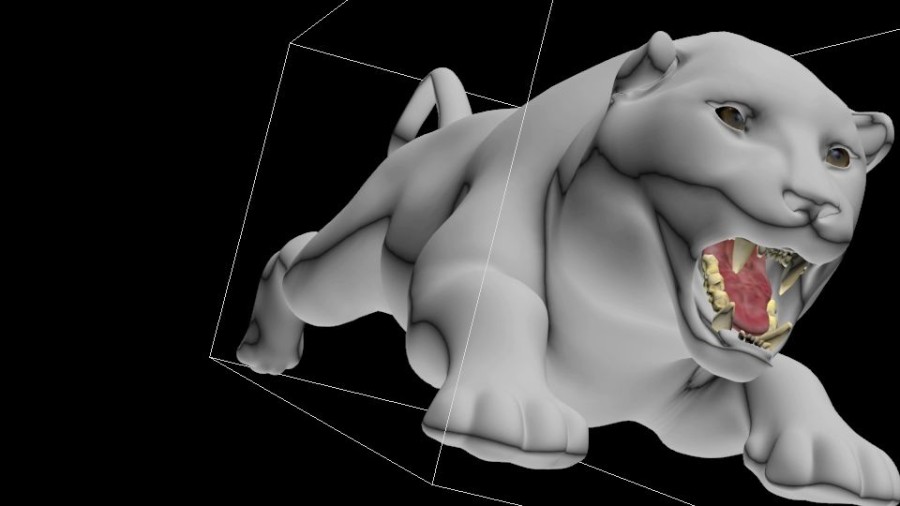

Chia-Wei Hsu’s video installation Spirit-Writing (2016) is the second work the artist has devoted to a frog deity, allegedly born in a small pond more than 1,400 years ago in Jiangxi, China, whose original temple in Wu-Yi was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. As a result, Marshal Tie Jia, as the deity is named, was forced to migrate, eventually settling on an island in the Taiwan Strait. There, it has continued to communicate with local villagers via a divination ritual that involves them carrying a divination chair, through which the Marshal makes his declarations both in writing Chinese characters and through knocking sounds. The work consists of a performance of this ritual, recorded in a “green room” equipped with multiple cameras and sensors for the purposes of motion capture. The artist invites the deity to tell the story of his displacement. And this displacement is mirrored in the technological setup. The sensors and cameras capture the movements of the divination chair, and place it in the abstract Cartesian space of a digital 3D grid. The villagers who carry the structure are left out of this transposition.

Chia-Wei Hsu, Spirit-Writing, 2016, 9:45 min. (film still), produced by Le Fresnoy, Co-producer: Liang Gallery.

© Chia-Wei Hsu

In the session, Hsu explains the process of making Spirit-Writing to the deity, and interrogates it about the shape of the destroyed, original temple, which the artist then also reconstructs as a wireframe model. This digital simulation is shown simultaneously with the “green-room” performance, but on the opposite side of the screen. While one side documents the divination ritual, where the villagers as well as the artist engage Marshal Tie Jia, the other side shows the transposition of deity and temple into a virtual space of digital coordinates, enabling a de- and re-contextualization. It is as if the simulation also presents a quasi-spiritual counterpart, the “other world,” in which the deity might reside, and in which lost landscapes from a missing past can be reconstructed and reanimated. The digital space acts as a refuge for the victims of modern forms of iconoclasm, the destruction of Chinese traditions during the Cultural Revolution.

There is both a vivid sense of uprootedness and abstraction transmitted by the object floating in the 3D rendering, and an uncanny sense of ghostlike levitation. The oscillation between uncanniness and abstraction serves to inflate and conflate the difference between digital media and spirit media, and it is worth looking into the “green screen” technique used by Hsu to induce the displacement.

Chia-Wei Hsu, Spirit-Writing, 2016, 9:45 min. (film still), produced by Le Fresnoy, Co-producer: Liang Gallery.

© Chia-Wei Hsu

Green screen, or “chroma key,” is a generic technique used in film to create a homogenous background for an image that, in the editing room, can be replaced with a different scene. It is a method of extraction, severing a thing from its milieu and inserting it into whatever desired new context. As a paradigmatic image-technology, it mirrors modernity’s powers of displacement, which are known to de-naturalize the originary relationship between an organism and its environment. Indeed, the green screen technique can be seen as an allegory of the ontological upheaval whose name is modernity. “Ground” ceases to serve as a guarantor of a primordial stability, and loses its “natural givenness,” which once tied each “spirit” to a certain context. This is perhaps the most fundamental sentiment of modernity: the loss of ground, the alienation from the environment. And it is this broken link that exposes our existence as mediated.

Chia-Wei Hsu, Spirit-Writing, 2016, 9:45 min. (film still), produced by Le Fresnoy, Co-producer: Liang Gallery.

© Chia-Wei Hsu

Spirits are typically at home in particular places. So what does it mean for a displaced frog deity to be given a second home in a temple reconstructed as digital-3D simulation? From one perspective, it appears as if the deity is trapped in a form of representation firmly entrenched in a Cartesian conception of abstract, geometric space in which discrete entities reside or move. Emblematic of a certain modern rationality, such a conception of space can be diametrically opposed to an understanding of space as relational and performative, brought into existence by the very bodies that inhabit it. The space on the documentary side of Hsu’s screen—the one in which the artist interacts with the villagers and the deity—is perhaps best described as a space in that latter sense, a laboratory of mediation, testing the potential to widen the “community of language” (in this case, to non-human spirits), and what is left of a mediation such as a divination ritual or “local spirits” in conditions of displacement. And what is a divination ritual if not an attempt to connect with the “grounds” of mediality, to “read what was never written”? But at the same time, that displaced, groundless, and experimental ritual is inscribed into a new frame on the opposite screen, that of Cartesian, digital space, which itself is a meta-medium, as it makes all spaces commensurable to each other by effacing their singularity and difference. The “green screen” and the 3D simulation on the respective sides of the screen seem to suggest that spirits have become placeless and hence their figuration, the form in which they might become articulated, has become uncertain. This uncertainty and openness with regard to the possibility of media, whether human, technology, or other, it seems to me, is one of the signatures of modernity. The effacement of difference, on the other, and the inscription into the grid of universal meta-media of abstraction, is another. To a certain degree, GPS and related technologies make clear that this Cartesian space has become a planetary envelope. Can the frog deity and its “wild transmissions,” hovering, and yet entrapped in the digital space, serve as an allegory for our current condition at large?

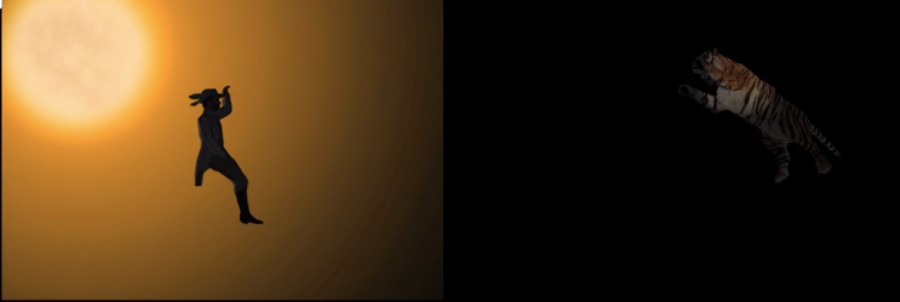

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

In Ho Tzu Nyen’s work, the planetary dimension of this double-edged space of mediation appears in a different register. Ho has been working on the histories of the tiger in the Malay world for several years, tracing the place tigers hold in a radically transforming cosmology—as co-species, mythical symbols, and ghosts that haunt the imaginary of modernity. In most areas that humans shared with the tiger, mythology reflects their status as “liminal” animals, closely related to the human community, and yet demarcating it from the outside—as an animal-other, but as a medium and symbol for relations that cannot be otherwise pictured as well. Exploring these histories, Ho Tzu Nyen’s work departs from the stories of weretigers: those shape-shifting beings crossing the ontological boundary separating the human from the animal, thus mediating the limits of what it means to be and belong to the human. In Malay cosmology, weretigers were communicating with the world of the ancestors and spirits. It is both to ancient mythology and to the ghostly returns of the tiger in twentieth-century modernity, that Ho devotes his narrative. Recovering from the nationalist phantasm the anti-essentialist reality of fluid identities, he taps into the transformative potential of this “medium” and traces the tigers’ spectral returns.

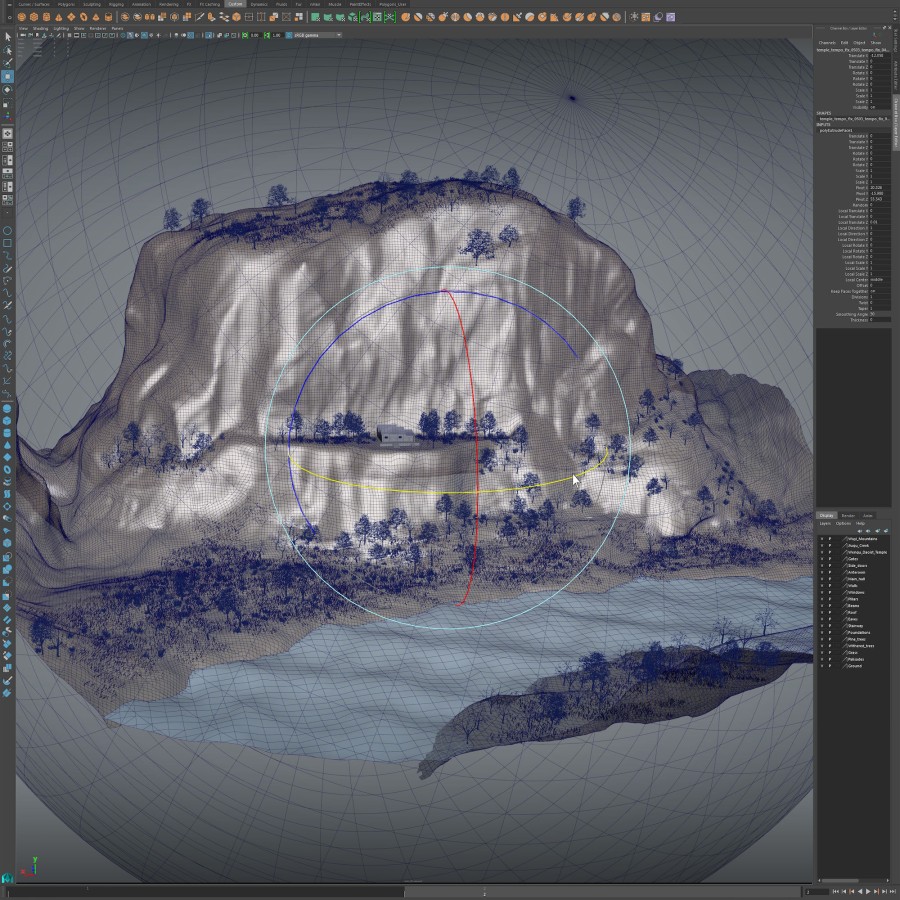

Ho Tzu Nyen’s One or Several Tigers (2017) takes its cue from a lithographic print titled, Road Surveying Interrupted in Singapore (c.1865‒85), executed by German illustrator Heinrich Leutemann. The lithograph shows George Dromgold Coleman, Government Superintendent of Public Works and Land Surveyor of Singapore for the British in the 1830s, who was also in charge of the islands’ convict workforce, at work in the jungle with a group of prisoners, as they are being attacked by a tiger. In the center of the image is a theodolite, the tool used for the land survey.

The lithograph depicts the “primal scene” of colonial history, the opening up of the “wilderness” by surveying the land. Yet it also shows how this wilderness, being pushed back and “tamed,” strikes back. The toppling theodolite, the recoiling humans, all held in suspense, floating aloft: the image is an allegory for the rupture of colonial modernity. And as variously noted, the tiger in this scene does not attack Coleman or the convicts that assist him. Rather it strikes at the theodolite. Ever since the process of enclosure in Europe in the early days of capitalism, surveying the land by means of triangulation has been crucial for taming and subjugating the wilderness and advancing the property regime. The survey is the initial step in a chain of abstractions that allow modern forms of administration to exploit the land from a distance, profoundly transforming and “ungrounding” local ecologies and hierarchies. This act of abstraction transforms the land “from ground into an equipotential datum” (Le Corbusier), and is another form of modern ontological drift, a form of displacement and “groundlessness.” And this labor is begun by the theodolite.

Index to the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (1922). Source: Government of India, Report of the Survey of India for 1921‒22. Image in the public domain provided by Wikimedia Commons

The habitat of the tiger is pushed back to make place for plantations.2 In the larger historical context, it was around plantations that an entire system of measuring and mapping, quantification and standardization emerged. Designed to organize nature and police humans in order to increase their productivity and extract wealth, this system, arguably also the basis of the modern factory regime, resulted in the global circulation of goods and abstractions. Termed “immutable mobiles,” these abstractions comprise inscriptions and measurements that can travel any distance without being transformed themselves,3 and we must count among them the ultimate medium: money. Today’s Singapore, one of the Four Asian “Tiger States,” is emblematic of a modern polis devoted to the universal circulation of the material and the immaterial.

That theodolite that penetrated the jungle announced the coming universal language of administrative abstraction, the arrival of a vast web of mathematical operations and bureaucratic procedures, which has been growing exponentially over the past centuries, and has culminated in the information technologies in use today. At the time of George Coleman, this “grid” of modernity was virtually identical with the breadth of Empire. Yet the imperial frontier was still earthbound and linear, enclosed by an outside that was unknown. The web initially woven by the theodolite has been extended by thousands of satellites orbiting Earth.

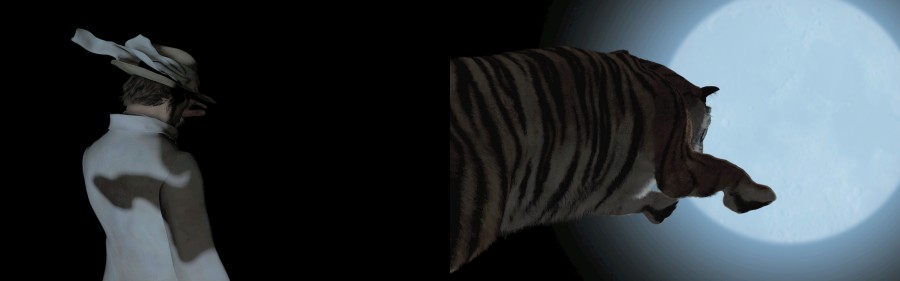

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

One or Several Tigers is also a reflection on the history of cinematic animation. If the weretiger is a figure that destabilizes ontological divisions in crossing the domain of the animal to the human, and the world of the living and the spirits, the animated image too derives its very animation equally from transgressing those boundaries. Yet what are these two manifestations of ontological crossing revealing about the historically changing nature of the boundaries thus crossed? Cinematic animation, from its origins to recent computer-generated imagery (CGI) films such as Avatar, has always been a medium of anarchic mediations, of shape-shifting, and particularly, of human‒animal metamorphosis. Its physiological, synesthetic effects on the human sensorium cut deep into the strata of our evolutionary becoming, activating the metamorphic realm before meaning and language, its condition of possibility. Apparently, for humans, the milieu of language, of the pre-linguistic grounds of language, cannot be circumscribed without the animal metaphor. This perhaps verifies what is frequently stated in animist myth: namely, that humanity owes its “humanity” and language, to the animal. The stories told of how that evolutionary debt was created, however, differ widely.

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

It is into the planetary orbit, into empty space, that Ho Tzu Nyen has hence “displaced” the now-mythical figures from the lithograph showing the tiger attack. In the digital animation of One or Several Tigers, all elements of the original scene re-appear, except the initial “backdrop”: the jungle. Instead, the individual figures—namely, Coleman, the colonial subjects, and the tiger—float, displaced, within space, like a celestial constellation, upon which Ho’s modern cosmology rests. As if unchained from the Earth, plunging backward, sideways, forward, in the cold light of undead time, the synthetic, spectral bodies of human, animal, and the human‒animal hybrid, have been literally ungrounded. They seem to echo Nietzsche’s madman who shudders with his lantern confronted with the modern abyss allegorized by the “breath of empty space.”

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

Ho thus exposes and makes thematic the genre of cinematic animation, and the status of CGI imagery in particular, suggesting that it might serve as an allegory of our present cultural imaginary of the planetary technological condition. But the groundless ontology of this cosmos is haunted. And while haunting might symbolize the porosity of ontological divisions (chiefly, between death and life), it also typically holds reality hostage. Animation is double-edged: on the one hand, the medium of animation suggests an ontological omnipotence: an entity can assume any form, can transgress any boundary, even death is reversible. On the other hand, this limitless possibility is bounded by impossibility: genuine invention is frequently jeopardized by the reification of normative schemes of perception, managed within the matrix of the colonial imaginary, as if under its spell. In this sense, the fate of animation as a popular genre, too, is symptomatic of modernity and of modernism. In its early days, modernist animated film explored the “zero point” of mediality, the animated line drawing was capable of morphing freely, taking none of the ontological divisions and frames on which modern and colonial knowledge rested for granted. In this, early modernists realized a critique of class and of subjective expression, as they saw nothing less than the “chance to return to the drawing board of social formation.”4 But the ability of the animated image to traverse the horizon of possible transformations was rather quickly inverted under pressure of commercialization, and turned into a tool for surveying normative perception geared towards new standards of mass production. In the place of the unbounded morphism and groundless alterity capable of revolutionizing bodily standards, anthropomorphism, based on principles of identification and projection of self, became the rule. Must we hence imagine cinematic animation not only in the modern analogy to a pre-modern, magic, and enchanted world of anarchic medialities, but as its symptomatic displacement? Could we imagine the technology of animation to be a product of the spell cast by the theodolite?

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

The animated image is itself the product of a dialectics of capitalist modernity. The technology to produce the illusion of movement is the result of its rationalization, not least for the purposes of organizing bodily gestures in the factory.5 In CGI, this dialectics underlying modern animation is pushed to new heights: CGI is no longer a representation that exists in utopian friction with that which it represents. Rather, it is a data-map. Animation is thus not achieved as a counter-gesture or line of flight from the fixating grid, but rendered through its finest possible resolution: the growing leaves of a tree, for instance, are typically produced nowadays by generative algorithms modeling evolution itself. There is, figuratively speaking, no longer a tiger that attacks the theodolite as its antithesis, but rather, it is the theodolite itself that assembles, or conjures up, the likeness of the tiger from countless data-points. The difference is not merely between abstraction and flesh, between safe distance and threatening proximity, eye-level encounter and action-at-a-distance: the very dichotomies whose collapse is dramatized in the lithograph of the tiger attack.

Ho Tzu Nyen’s cosmography dramatizes no such collapse; rather, it subverts the dominant aesthetics of CGI blockbusters by pointing to the ambivalence of its clichés of romantic enchantment and archaic magic: where everything seems possible, no actual transformation can occur, outside the given matrix of a historical imaginary. If the animated image once (and paradoxically) revived an ancient animism—an antecedent and universal mediality, in which everything can potentially act as a medium of everything else—then this very same ontological anarchy and universal mediality, today, speaks of a different condition: that of a universalized Cartesian envelope, in tandem with capitalism’s fantasy of a dematerialized universal mediality, achieved through digital code and its union with the medium of money. CGI might then be symptomatic of a permanently reconfiguring capitalism that does not know how to die. The animation of One or Several Tigers is, not least, an arresting manifestation of this dialectics. And it is a manifestation that is perforated: in several instances, unexpectedly the screen of video projection is lit from behind or disappears altogether, to reveal a shadow theater, in which the characters of the lithograph are rendered as puppets—paying tribute to an unbroken local vitality of the live arts and the (shadow) theater, and exposing the fragility of hegemonic, dominant media.

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

One or Several Tigers is named after the chapter titled “One or Several Wolves?” In the book A Thousand Plateaus (1980) by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari—a book that seeks to liberate the mediality of the psyche from its Freudian enclosure in the interior of the individual self. Against the psychoanalytic focus on the nuclear family as the stage on which the psyche is formed, Deleuze and Guattari advance the concept of a “machinic assemblage,” of the psyche existing in multiple associations with other forces and beings, putting forward an exteriorized, “machinic” conception of the unconscious and its anarchic and “asignificatory” mediality. In this chapter, Deleuze and Guattari depart from a patient of Sigmund Freud who has come to be known as the wolf-man. Freud’s analysis revolved around a dream that Sergei Pankejeff had at the age of five, in which several wolves sitting on the branches of a tree were staring at him, inducing a lifelong fear of wolves along with depression and anxiety and phobia. Freud deciphered this dream as a rendering of a primal scene, having witnessed his parents copulating. For Deleuze and Guattari, it is precisely this reduction to the oedipal family drama, which is symptomatic of Freud’s enclosure of the mediumistic psyche, and of Western reason’s incapacity to think multiplicities (“several wolves,” a wolf “pack”) in general.

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

There are other associations here, which help further illuminate Ho Tzu Nyen’s work. Not only is a counterpart to the weretiger in Europe, the werewolf, equally marking the limits of human society, both dividing and mediating humanity and animality, order and wilderness, but also the living and ancestry, the human and the divine. The relation between the two species in each case refers to a mythical time anterior to the human order and to rationality, as we know it: a time that we cannot but imagine as a primordial mediality and which is hence frequently cast as origin, and projected into a distant past. Access to such a primordial terrain of mediality anterior to the ontological divisions that structure everyday perception is of an initiatory character: hence the importance that human‒animal metamorphosis and shape-shifting has in spiritual, and particularly in shamanic traditions. A shaman’s healing powers are typically derived from such mediumistic capacity, a capacity that reaches beyond the human, beyond the mediated social existence of a particular society, and can thus act on it. One would typically become a shaman through undergoing a controlled mental crisis (equivalent to a psychosis in the language of psychiatry). But whereas such crisis today is being privatized in institutional medicine (it is identified as an individual’s sickness, relegated to the inner self of that individual), in such initiation it is being exteriorized, dissociated, from the person, and formally identified as a certain external force or “spirit” that, under certain ritual conditions, possesses the person in question. When the historian Carlo Ginzburg analyzed the imaginary of the wolf-man and his recurring dream of wolves sitting in a tree and starring at him, he thus discerned a “nightmare of an initiatory character,”6 which corresponded with folktales over centuries. In this dream, a certain ontogenesis of culture is transhistorically activated: it is a form of remembrance of what otherwise cannot be remembered, namely the exclusions and experiences which are constitutive of human society as a negative imprint; what Michel Foucault called, with respect to the “discourse” of madness, the face of a culture’s positivity.7

A werewolf or weretiger is a medium at the limits of a social body, a figure traversing the liminal. In the privatized individual psyche, these limits, and their collective origin, and hence the mediated nature of subjectivity as such, goes unacknowledged. According to Ginzburg, “the wolf-man’s fate differed from what it might have been two or three centuries earlier. Instead of turning into a werewolf, he became a neurotic on the brink of psychosis.”8 Similarly, a weretiger in the Malay world today would likely end up in psychiatry—if we ever came to even know of such mediumistic aptitude.

We can think of the works of Ho Tzu Nyen and Chia-Wei Hsu perhaps as outright inversions of this enclosure of mediumistic phenomena. Their juxtaposition of “old” and “new” media points to the colonial unconscious undergirding their separation, but it also stresses that the colonial assault on non-modern cosmographies and non-capitalist economies set loose, is ongoing and intensifying. And even while this might have become less immediately recognizable, perhaps because its main agents are often no longer explicitly stated ideologies such as colonialism or nationalisms, now rather it is the technological applications that inadvertently naturalize ontological templates derived from the colonial modern frontiers. And they underline what Walter Benjamin, with a clairvoyant eye for historically transforming means and medialities, has diagnosed: namely that “magic” and “technology” are historical variables. And in a similar vein, this counts for the border between the inner self and the outer world, and between the collective and the individual.

There is no search for a missing phantasmatic ontological security, for lost origins in these works. Even when they present stories of origin, they do so in order to open up the present, in an embracing of difference, and an attempt to articulate and speak through this difference historically. It is a zone of becoming that is invoked here, a reality that consists of multiple layers of emergent complexity, an ontology of unruly mediations. But there is also an insistence that such an anti-essentialist, and realist ontology of becoming—of porous membranes and multiplicities rather than contained entities and borders—must be articulated through precise historical topologies, which battle against the short-circuit of symptomatically imputed essentialist truth-claims by opening up the historical space of mediation and histories of meaning.

Ho Tzu Nyen, One or Several Tigers, 2017 (film still).

© Ho Tzu Nyen

Ho Tzu Nyen traces the shifting meanings of the tiger as a floating signifier across such a topography. His delirious narrative is equivalent to an “initiatory dream,” a dream dreamt for the purposes of rendering a history of segregation and private enclosure public and collective again. In the work, the tiger-symbol moves from being a mediator of the ancestor world, to symbolizing both the threat of chaos and of domination, to impersonating imperial and capitalist predation. In the second part of One or Several Tigers, Ho intensifies the dialectics of animation. Is terror, this “rational” rule of the arbitrary, this spectral underside of modernity’s reason, this undoing of the order of the heavens and the Earth not the underbelly of animation’s enchantments? The work both breaks through the web woven by the theodolite, the planetary data-envelope, and at the same time, knits it even more tightly. Ho does so by turning to the group of convicts shown to surround Coleman the surveyor in the lithograph of the tiger attack. While we listen to Ho telling us the story of Indian convicts in Singapore being charged with building their own prison, where eventually they would become each other’s wardens, and surveillance was gradually replaced by self-surveillance, we watch real actors impersonating the convicts surrounding Coleman, as their bodily gestures are motion-captured and scanned for 3D CGI-rendering by eighty-two cameras simultaneously. The situation depicted here is an inversion of what Benjamin described with regard to early photography and moving images, namely that they “restored gesture to the human technology of recording experience.” Now these gestures, these bodies, feed machines to lend them a human face.

Thus the “ghostly labor” on which Singapore, and colonial moderinity in a wider sense, has been built, makes its appearance. The laborers depicted in the lithograph were convicted felons from India under British rule. They referred to their journeys overseas as a voyage through “black waters,” gradually dissolving their identity and destroying their past life, like “water in water.” The motif of “crossing” and shape-shifting, mirrored by the relation between the mythical weretiger and the medium of animation earlier, is re-signified here once more. What the suspense in “space” was for the CGI animation of Coleman and the weretiger, is now mapped onto colonial history and the passage across the ocean, allegorizing the process of displacement and identity-dissolution—the effacement of difference, and of history. This dissolution of identity is at once an irretrievable loss and a potential—as “water” can stand for a zone of becomings, a medium of unruly mediations, or alternatively, for the subsumption of everything under modernity’s master medium, capital. The tipping of the dialectic hinges on that difference between different medialities, like “water” or “water”—a difference under threat of collapsing once and for all, just as the memory of the past for Benjamin, flashing up only in “moments of danger,” like light refractions in water. And such a moment of danger was the encounter between Coleman and the tiger, a flashing up of danger. Ho projected them into cosmic space, mirroring capital’s dream of overcoming the bounds of matter. “Water in water” stands for the vanishing difference between techno-capitalism’s fantasy of a universal mediality, and the search for different forms of global commonality in the ruins of imperial universal history. Thus, in the next instance, we see the actual bodies impersonating the prisoners confronting the print of the tiger attack in a museum: specters made real, looking across the divide, thus pulling into doubt just who and what is real here and what a ghost. The historical topography laid out here is about the insistence on difference, the unambiguous, essentialist fixation of identity through state power, yet equally opposed to the conflation of the “zone of becoming” with the mobility of capital, and the latter’s liquefication of identity and dissolution of stable borders. It is a topography that sees in images above all that which resists mediation, insists on difference, and thus opens the potential for communalities that are not based on identification.

An excess of mediality is characteristic of our species. The mediumistic dimension of human existence is the apriori condition for our ability to construct systems of signification, but it cannot itself be signified, at least in a positivist fashion. The being-in-a-medium-of-communication of our subjectivity, tends to elude us. It can be exposed, but only at the price of all absolute certainties, instead letting the full forces of ambiguity that characterize our socially mediated existence come to the fore. And always only from one subject to another, and through transposition of one medium into another. We might have to remain silent about what lies beyond the grasp of language, but images, for instance, can capture these limits precisely by dwelling on the difference between picture and word. What can and cannot be communicated by a specific medium can only be grasped in a different one.

This transposition from one medium into another enables a binocular vision, according to which every division is also a space of mediation. Here, every line can be turned into a volume, an “objective zone of indistinction.” It is this transformation from border into medium that the artistic image effects: the destabilization of the difference between what is real and imaginary. This invokes a sensibility for histories of the psyche and its transhistorical temporality, so closely linked to aesthetics as a crossroads of mediations and embodiments. It can espouse the notion that our psyche is a medium (to paraphrase Henri Bergson on the body) of which we do not know what it can do. Modernity, therefore, is also the name given to the quasi-mythical experience: without an anchor in any definite, stable reference, the world originates in mediation, as if from the middle. This makes a universal history of borders or limits thinkable, and necessary, as sedimented in images. It is a history that is never universal in a positivistic sense—rather, a “negative” history, exposed only through unruly mediations on modernity’s spectral underside. Contemporary art has the power to claim this spectral underside as ontological reality. A key to modern knowledge is the realization that we do not know what kind of media we are and can be.

Lieko Shiga, from the “Rasen Kaigan” series, 2009.

© Lieko Shiga

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Art Review Asia, March 2017.

This reading is indebted to “An Iconography of Mediumism”—a project by Heinz Schott, Ehler Voss, and Erhard Schüttpelz for the exhibition Animism at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), Berlin, 2012, published in conversational format as “Heinz Schott, Hieroglyphensprache der Natur. Ausschnitte einer Ikonographie des Medienbegriffs,” in Irene Albers and Anselm Franke (eds), Animismus. Revisionen der Moderne. Zürich: diaphanes, 2012, pp. 173‒95. Furthermore, I owe inspiration and several arguments in tackling the question of “mediumism” to Erhard Schüttpelz, especially the article “Koloniale und postkoloniale Trancemedien,” in Ulrike Bergermann and Nanna Heidenreich (eds), total. – Universalismus und Partikularismus in post_kolonialer Medientheorie. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2015.

Kevin Chua, “The Tiger and the Theodolite: George Coleman’s dream of Extinction,” and Ho Tzu Nyen, “Every Cat in History is I,” in Broadsheet: Contemporary Visual Arts+Culture, vol. 36, no. 2 (June 2007). Both texts are reprinted in edited versions in this publication.

Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Esther Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands: Animation, Critical Theory and the Avant-Garde. London and New York: Verso, 2004. p. vii.

See: Edwin Carels, “Biometry and Antibodies: Modernizing Animation, Animating Modernity,” in Anselm Franke (ed.), Animism (Volume 1). Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010, pp. 57‒74.

Carlo Ginzburg, Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990, pp. xvii, 231.

Michel Foucault, Madness and Unreason. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1972.

Ginzburg, Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990, p. 134.

1. This reading is indebted to “An Iconography of Mediumism”—a project by Heinz Schott, Ehler Voss, and Erhard Schüttpelz for the exhibition Animism at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), Berlin, 2012, published in conversational format as “Heinz Schott, Hieroglyphensprache der Natur. Ausschnitte einer Ikonographie des Medienbegriffs,” in Irene Albers and Anselm Franke (eds), Animismus. Revisionen der Moderne. Zürich: diaphanes, 2012, pp. 173‒95. Furthermore, I owe inspiration and several arguments in tackling the question of “mediumism” to Erhard Schüttpelz, especially the article “Koloniale und postkoloniale Trancemedien,” in Ulrike Bergermann and Nanna Heidenreich (eds), total. – Universalismus und Partikularismus in post_kolonialer Medientheorie. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2015.

2. Kevin Chua, “The Tiger and the Theodolite: George Coleman’s dream of Extinction,” and Ho Tzu Nyen, “Every Cat in History is I,” in Broadsheet: Contemporary Visual Arts+Culture, vol. 36, no. 2 (June 2007). Both texts are reprinted in edited versions in this publication.

3. Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

4. Esther Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands: Animation, Critical Theory and the Avant-Garde. London and New York: Verso, 2004. p. vii.

5. See: Edwin Carels, “Biometry and Antibodies: Modernizing Animation, Animating Modernity,” in Anselm Franke (ed.), Animism (Volume 1). Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2010, pp. 57‒74.

6. Carlo Ginzburg, Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990, pp. xvii, 231.

7. Michel Foucault, Madness and Unreason. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1972.

8. Ginzburg, Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990, p. 134.